Can a child go up to the duchan? It’s a simple question that merits a simple answer. Fortunately, Hazal gave us one (Mishnah Megillah 4:3):

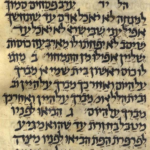

קָטָן קוֹרֵא בַּתּוֹרָה וּמְתַרְגֵּם, אֲבָל אֵינוֹ פּוֹרֵס עַל שְׁמַע, וְאֵינוֹ עוֹבֵר לִפְנֵי הַתֵּיבָה, וְאֵינוֹ נוֹשֵׂא אֶת כַּפָּיו.

In as many words (or, to be precise, fewer), the Mishnah tells us that a child cannot perform Bircat Cohanim. The minimum age for a Cohen to participate therefore is 13 or, at the very least, is no less than 13. I add the latter advisedly because the Tosefta (Hagigah 1:3) adds another qualification:

כן תינוק שהביא שתי שערות חייב בכל המצות האמורות בתורה ראוי להיות בן סורר ומורה נתמלא זקנו ראוי ליעשות שליח צבור לעבור לפני התיבה ולישא את כפיו [אבל] אין חולק בקדשי מקדש עד שיביא שתי שערות רבי אומר אומר אני עד שיהא בן עשרים

A boy becomes obligated in mitzvot when he grows two pubic hairs, which will normally happen in time for his 13th birthday. 1 However, in order to take on the role of leading prayers or performing bircat cohanim, mere adulthood is not enough: he must first reach a more advanced stage of development signified by having a full beard. The same baraita appears in almost identical language in the Bavli (Hullin 24b), where it is quoted for the purpose of analyzing the final dispute about qadshei miqdash.

Taking into account both sources, there are three ways to answer the question of how old a cohen must be to bless the congregation.

- The Mishnah and baraita disagree and the halacha follows the Mishnah. Therefore, a cohen may perform Bircat Cohahim from his 13th birthday onwards, assuming he has two pubic hairs.

- The Mishnah and baraita disagree and the halacha follows the baraita. Therefore a cohen may perform Bircat Cohanim only once he is able to grow a full beard.

- The Mishnah and baraita do not disagree. The Mishnah gives a list of activities that a qatan cannot perform, but it does not follow that he is permitted to do them immediately upon ceasing to a be a qatan. In fact, as the baraita informs you, he must wait until he is able to to grow a full beard.

Practically speaking, the second two approaches amount to the same thing and this is a good reason for erring on the side of caution and not allowing a cohen to duchen until he has a proper beard. One could, however, argue that since the requirement of a full beard is absent from the Mishnah, and that since the baraita is quoted in passing by the Bavli in the context of a quite different discussion, it is therefore improper to deny a young man the opportunity to perform a mitzvah for the better part of decade based on a non-authoritative source. This is a matter about which reasonable men might be expected to disagree and we find that reasonable men do, in fact, disagree about it. Rambam (הלכות תפילה טו:ד ), Rif, and the Behag all rule that a full beard is a requirement for Bircat Cohanim, while Rav Amram Gaon2 mentions no such qualification.

A dispassionate look at the sources and the response to them by the Geonim and early Rishonim, then, would probably lead one to the view that, normally, only those with full beards should perform Bircat Cohanim, but with room to permit younger adults to do it in extenuating circumstances3. And that would be that, except for a baraita quoted right at the end of Bavli Succah chapter 3:

ת”ר קטן היודע לנענע חייב בלולב להתעטף חייב בציצית לשמור תפילין אביו לוקח לו תפילין יודע לדבר אביו לומדו תורה וק”ש תורה מאי היא א”ר המנונא תורה צוה לנו משה מורשה קהלת יעקב ק”ש מאי היא פסוק ראשון היודע לשמור גופו אוכלין על גופו טהרות לשמור את ידיו אוכלין על ידיו טהרות היודע לישאל ברשות היחיד ספיקו טמא ברשות הרבים ספיקו טהור היודע לפרוס כפיו חולקין לו תרומה בבית הגרנות היודע לשחוט אוכלין משחיטתו

The baraita lists the different ages at which a father should start training in son in various mitzvot. Second to last in this list is a cohen receiving terumah and the baraita specifies that this should be done when he knows how to ‘spread his palms’, that is to to say, to perform Bircat Cohanim. However, as we have seen, both the Mishnah and the Tosefta-baraita are quite clear that children may not perform Bircat Cohanim. What can it possibly mean, then, for this baraita to use the ability to perform Bircat Cohanim as a test of readiness for an infant?

At this stage, enter the ba’alei Tosefot who approach the issue from a totally new perspective. So far, we have assumed that the two sources which discuss the minimum age for Bircat Cohanim are discussing the same thing. If this is so, they might be taken to be contradictory, or just as plausibly, to be complementary (one states that one must have a full beard to perform the mitzvah, whereas the other one excludes an infant from doing so without specifying what the minimum age is). The baraita in B Succah, then, does not fit with either of the other two sources. Tosefot, however, look at each of the three sources as equally authoritative and also assume that they must be perfectly compatible. They resolve the problems that these assumptions throw up by positing that the three sources are actually talking about three different cases:

ואין נושא כפיו – משמע הא אם הביא ב’ שערות ישא כפיו וקשה דהא סוף פ”ק דחולין אמר דאין נושא את כפיו עד שיתמלא זקנו ועוד קשה דמשמע סוף פרק לולב הגזול קטן היודע לישא את כפיו חולקין לו תרומה בגורן ואפילו קטן ממש וי”ל דההיא דלולב הגזול מיירי עם כהנים גדולים ללמוד ולהתחנך והא דפסלינן הכא קטן מיירי בשאין גדולים עמו וההיא דחולין דבעי מלוי זקן מיירי לישא כפיו תדיר בקביעות אבל באקראי בעלמא יכול הוא לישא כפיו אע”פ שלא נתמלא זקנו כדי לאחזוקי נפשיה בכהני:

Tosefot’s reconciliation of the the three sources is as follows:

- A qatan may not perform Bircat Cohanim on his own (or with other minors), but may join in with the Bircat Cohanim of adults.

- An adult who has produced two pubic hairs may perform Bircat Cohanim on his own but only on an occasional basis.

- An adult who has a full beard may perform Bircat Cohanim on a fixed basis.

This interpretation was evidently considered to be an important achievement. It is found in four places in the standard editions of Tosefot: on the Mishnah in Megilah, on the baraita in Hullin, on the baraita in Succah and on another baraita in Yevamot (99b), which we shall have occasion to look at shortly. It was recorded without demurral by Rashba, Mordechai, Rosh, Ritva, Tur, Ran, and finally the Beit Yosef, whose ruling in the Shulhan Aruch is as follows (OH 128:34):

קטן שלא הביא שתי שערות אינו נושא כפיו בפני עצמו כלל אבל עם כהנים שהם גדולים נושא ללמוד ולהתחנך ומי שהביא שתי שערות נושא את כפיו אפי’ בפני עצמו ומיהו דוקא באקראי בעלמא ולא בקביעות עד שיתמלא זקנו שאז יכול לישא כפיו אפילו יחידי בקבע

This, then, is the normative halacha and it is common, as a result, for children of six years old and upwards to participate in Bircat Cohanim with their adult brethren. Let us take a step back, though, and make a number of fairly obvious points about what we have seen so far.

First, the interpretation of Tosefot effectively reverses the ruling of the Mishnah according to which a qatan cannot perform Bircat Cohanim. Cohanim make up about 5% of the Jewish population and at least one can usually be found in most synagogues. More pertinently, though, priestly status is hereditary and, as a general rule, a minor in a synagogue will be there with his father. According to Tosefot and all those who followed their ruling, then, what appears to be a blanket rule actually only applies to a tiny minority of cases in which a child is present in a synagogue without other cohanim and unaccompanied by his father or any other adult male relative on his father’s side.

Secondly, Tosefot’s interpretation is a rather odd combination of, on the one hand, close textual reading, and, on the other, of assumptions that come out of nowhere and seem, not to put too fine a point on it, to be arbitrary and random. Tosefot buttress their claim about children joining in duchenen with reference to the practice of Levite children to sit between the legs of their adult brethren as they played music in the temple, but this parallel can scarcely be said to amount to an argument. Indeed, if one were to start from scratch and approach the sources according to Tosefot’s method, then one could come with a different set of postulates that would be just as plausible. Perhaps, for example, only adults with a full beard can say Bircat Cohanim on an ordinary day, but bar mitzvah boys can join in on Shabbat and children can participate on fast days.

Thirdly, if we look closely at the baraita in Succah upon which Tosefot’s argument hinges, something very odd emerges. For every mitzvah, the age of hinuch corresponds logically to the capabilities of the child: a boy takes a lulav when he knows how to correctly shake it; he wears tzitzit when he knows how to put on a tallit, he wears tefillin when he knows how to look after them etc. One example, however, stands out like a sore thumb, that of a child who knows how to ‘spread his hands’ being allotted terumah at the threshing floor. Not only is the activity not matched to the capability of the child, it is, on the face of it, totally mismatched: a ordinary seven year old can put his fingers in the air and say 15 words, but only a much older child can be trusted to take care of terumah without defiling it.

The problem with the baraita, then, is more serious that the one Tosefot identify, and their solution seems to violate Occam’s razor without enough in the way of explanatory benefit to compensate. Modern scholarship has, however, already solved the problem in a more satisfactory manner. Like the baraita in Hullin, the baraita in Succah has a matching equivalent in Tosefta Hagiga (1:3):

קטן שאין צריך לאמו חייב בסוכה קטן שצריך לאמו יוצא בעירוב אמו ושאינו צריך לאמו מערבין עליו מזון שתי סעודות בעירובי תחומין [יודע] לנענע חייב בלולב יודע להתעטף חייב בציצית יודע לדבר אביו מלמדו שמע ותורה ולשון קודש ואם לאו ראוי לו שלא בא לעולם יודע לשמור תפיליו אביו לוקח לו תפילין [כיצד בודקין אותו מטבילין אותו ונותנין לו חולין לשם תרומה] יודע לשמור גופו אוכלין על גופו טהרות יודע לפרוש [חוקו] חולקין לו על הגורן יש בו דעת לישאל ספיקו ברשות היחיד טמא ברשות הרבים טהור יודע לשחוט שחיטתו כשירה יכול לאכול כזית דגן פורשין מצואתו וממימי רגליו ארבע אמות כזית צלי שוחטין עליו [את] הפסח רבי יהודה אומר לעולם אין שוחטין [את] הפסח [עליו] [אא”כ יודע] הפרש אכילה [אמר לו] איזו הפרש אכילה כל שנותנין לו ביצה ונוטלה אבן וזורקה.

As is often the case with the Tosefta, the text here is extremely corrupt and the relevant words (יודע לפרוש [חוקו] חולקין לו על הגורן) would appear to be basically gibberish. This probably explains why the Tosefta is not cited by the Rishonim who followed Tosefot’s interpretation despite the obvious issues with the version in Bavli Succah. Fortunately, the issue has been solved by the greatest of the Aharonim, Shaul Lieberman, who showed that the correct reading is לפרוס חיקו, which solves all the outstanding issues. The baraita tells us that the age at which one allots terumah to a child at the threshing floor is the age at which he can spread out his garment in such a way to carry the grain in his breast. Since the baraita does not talk about Bircat Cohanim at all, the discrepancy between it and the other sources does not exist and clarity is restored.

There are though some loose ends to tie up. First of all, how do we get from the Tosefta to the girsa of the baraita in Bavli Succah? The relationship between baraitot that appear in the Tosefta and two talmuds is highly complex and it is difficult to say anything with certainty, however, three possibilities recommend themselves. The first is that the correct reading of the Bavli baraita is לפרוס כנפיו which is rough equivalent to לפרוס חיקו (and not necessarily any less authentic, though it may reflect Babylonian usage) and that the נ was lost in a familiar act of scribal carelessness. The problem is that there are precisely no textual records of such a reading. The second is that לפרוס כפיו is the correct reading of the Babylonian version of the baraita, but that it is here employed in a literal sense of putting out ones hands (to catch grain) rather than in a technical-euphemistic sense in which is refers to Bircat Cohanim. This is actually quite plausible since use of the formula פריסת כפיים is by no means common as a substitute for the usual נשיאת כפיים. The third is that the Babylonian version of the baraita is itself the product of a glitch in the oral transmission of halachot that were relevant in the land of Israel, but a theoretical matter in Bavel.

The next issue is why the Rishonim prior to Tosefot simply ignored the apparent problem of a baraita in Succah that seems to indicate that minors can perform Bircat Cohanim. While we cannot say for certain, the answer does not appear to lie in their having a superior text of the Talmud Bavli to ones available in medieval France. It is not even certain, and perhaps not even likely, that the girsa לפרוס כפיו is ‘incorrect’, let alone that an alternative reading survived to the Middle Ages. A close reading of Rambam (הלכות תרומות יב:כב) indicates that he corrected his reading of the baraita according to the Tosefta’s version, but this is certainly not true of the Behag or Rif who quote the Bavli’s version verbatim. The simplest explanation of why the Geonim and early Rishonim did not try to solve the problem thrown up by their version of the Talmud Bavli is that they did not notice it or, if they did, they did not think it needed solving. Not only Tosefot’s teirutz, but also their qasha, was based on a particular view of the Talmud, in which every line of every tractate must be studied and all parts made consistent with each other. According to the earlier method of talmudic scholarship, the fact that a baraita in Succah might appear to indicate that there are exceptions to a clear rule in Megillah and Hullin, might be considered interesting (or it might very well not), but it wasn’t sufficiently worrying to warrant creative speculation.

The final issue is why Tosefot’s interpretation was so widely and uncritically accepted. There are two observations to make here. The first is that the memorization skills and sheer amount of hard work that were necessary to draw up digests and commentaries in the absence of any system of cross referencing, or any kind of referencing beyond chapter titles, is beyond what any of us can imagine. I wrote this post having learned the sugya a few years ago and used Sefaria, Mechon-Mamre, Ctrl+f and Google search to gather together all the material. If I had only unpaginated manuscripts to work with, it would have taken me at least a day simply to track down the sources. Imagine doing this literally thousands of times just to finish a commentary on one Mesechta. There simply was no way to do this without, frequently, simply copying conclusions that had been made by earlier authorities.

The second observation is that when one unsatisfactory explanation exists for a particular problem, commentators are often moved to find a superior one, but when two exist they will tend to pick the least unsatisfactory one. Prior to Tosefot, the baraita in Succah had already been commented on by Rashi, who was troubled by an apparent contradiction with a baraita in Yevamot, which forbids distributing grain to a minor at the threshing floor:

ומקמי הכי אין חולקין לו בגורן אבל משגרין לו לביתו אם יודע לשומרה בטהרה דהכי תניא בגמרא דנושאין על האנוסה ביבמות עשרה אין חולקין להם תרומה בבית הגרנות חרש שוטה וקטן כו’ וכולן משגרין להם לבתיהם בבית הגרנות אין חולקין להם שבזיון תרומה הוא שאין כל רואיו יודעים בו שהוא בקי לשומרה אבל לביתן משגרין להם הבקיאים ומכירין בהם ומשיודע לפרוס כפיו ופורס בצבור הכל יודעים שהביא שתי שערות שאין קטן פורס כפיו כדאמרינן במגילה הלכך חולקין לו

Rashi’s explanation also solves the problem posed by Tosefot, and it is cited as as such by Ritva and Rashba, who both reject it as unconvincing, which, indeed, it is. By comparison, Tosefot’s explanation certainly works better as a local explanation of the baraita and was therefore adopted by subsequent authorities.

*

I hope by this stage, I have established that Hazal forbade children to perform Bircat Cohanim and that the process by which it became normal for them to do so essentially consists of a mistake based on an overreading of a talmudic baraita being repeated by one authority after another until its final codification. Those who are not convinced will not, I think, become so if I belabour the point. I will now turn to the wider issue.

Everyone who with experience of Modern Orthodoxy, broadly conceived, will have heard of something called ‘the halachic process’ which occupies a position roughly equivalent to that shared by mesorah and daas torah in the Haredi world. The concept has been explained in different ways, with diverse forms of philosophical and theological backing. I ask you, though, does the story I have told above look like ‘the halachic process’ as explained by any of the apologists for orthodoxy, even a little bit?

I will, then, offer my alternative reactionary thesis: ‘the’ halachic process doesn’t exist. It never happened. What did happen are thousands of arguments, which were resolved in different ways and at different time based on different considerations. Each case is unique and must be treated as such. The intelligent person’s response to each case must also be unique. For instance, if one wants to know why most Jews do not wear tefillin on Chol haMoed, the answer (simplified, but not by much) is that they all stopped because the Zohar says doing so makes you worthy of death. The question, therefore, of whether you should wear tefillin on Chol haMoed has nothing to with general principles of halachic ontology or epistemology, but with the specific question of who wrote the Zohar. Only by answering this question will you know whether to wear tefillin on Chol haMoed, and this will not help you one bit when you come to answer other questions in which the Zohar’s status, or lack of it, plays no role.

At this stage, though, there is one group of halachic process theorists who will pipe up and declare that their particular model is vindicated. This school argues that healthy halachic development occurs through a distributed, semi-democratic and *organic* process in which codification and close textual analysis play only a side role, important mainly for maintaining continuity at times of historical stress. They may, then, be tempted to argue that this small case study confirms their thesis: the halachic process goes wrong when it becomes too theoretical, too book-oriented, too much based in the study-house and not enough in the real world.

The problem is that in the story typically told by these theorists the halachic process was working pretty great until quite recently when some event (the publication of the Mishnah Berurah, mass exodus from eastern Europe, the Holocaust, a counter-reaction to secularisation, take your pick) knocked it off course. All that is needed is to reverse the yeshiva revolution and everything will be just fine. But what I am talking about happened nearly a millenium ago, when the Chazon Ish was but a twinkle in his great-great …. great grandfather’s eye. Whatever went wrong, it went wrong a long time ago.

Children participating in Bircat Cohanim is not, I think, a trivial problem. Anything about schul in which children participate loses its seriousness. We see this with אנעים זמירות, regarded by its author as the profoundest poetry on the nature of the Divine, now made into a cute family-friendly precursor to qiddush. All of us who have been in a synagogue in which a child participates in Bircat Cohanim have observed a similar phenomenon. Those who do not notice it cannot possibly appreciate what Bircat Cohanim is supposed to be.

Even those who disagree with me here, though, have to deal with the fact that this is not an isolated occurrence. The story, for example, of how the kezayit grew to its current gargantuan proportions (a source of wholly justified ridicule for opponents of orthodoxy that grossly disfigures 10s of 1,000s of Sedarim every single year) follows almost the exact same pattern as the one we have seen above. There are only so many broken parts you can point out before theories of your self-fixing car’s invincibility start to look beside the point. The ideological paralysis of Modern Orthodoxy is, of course, conditioned by the knowledge that the second the door is opened to intelligent reform, thousands of intelligent reformers stand waiting and eager to permit that which is forbidden and forbid that which is permitted. This is a function of Modern Orthodoxy’s cowardice, its refusal to say out loud that certain forms of reform are off the table because the Torah is not just a ‘religion’ in the sense the term is understood by Americans. But is doesn’t have to be this way. Things, it is true, could be a lot worse, but they could be a lot better too and no amount of kosherised Burke and Hayek can obscure the truth that better is better or make us entirely forget that G-d demands of us that we do our best.

Footnotes

- The standard halacha is that the time of obligation in mitzvot occurs when the boy has both grown two pubic hairs and has reached the age of 13, by which time the former qualification is almost always met. However, the Tosefta seems to take the view that it is solely dependent on the the emergence of pubic hairs and so will generally precede the boy’s 13th birthday.

- Regarding, a shliah tzibur, Rav Amram Gaon quotes Rav Natronai Gaon to the effect that the requirement of a full beard is lechathila and may be waved when no-one else is available.

- This is the opinion of Sefer Mitzvot Katan (קיב) (who argues that one who has produced two pubic hairs can perform Bircat Cohanim on an occasional basis) and Shiltei Giborim (who argues he can do it if the congregation does not consider it an insult to their honour).

Leave a Reply