To read this essay as a PDF click here.

וְכָל הַמַּאֲרִיךְ בִּדְבָרִים שֶׁאֵרְעוּ וְשֶׁהָיוּ הֲרֵי זֶה מְשֻׁבָּח

(משנה תורה הלכות חמץ ומצה ז:א)

The starting point for understanding the Maggid is the fourth halacha in the last chapter of Mishnah Pesahim:

מזגו לו כוס שני וכן הבן שואל. אם אין דעת בבן אביו מלמדו מה נשתנה הלילה הזה מכל הלילות שבכל הלילות אנו מטבילים פעם אחת הלילה הזה שתי פעמים. שבכל הלילות אנו אוכלים חמץ ומצה הלילה הזה כולו מצה. שבכל הלילות אנו אוכלים בשר צלי שלוק ומבושל הלילה הזה כולו צלי. לפי דעתו שלבן אביו מלמדו. מתחיל בגנות ומסיים בשבח ודורשים מארמי אובד אבי עד שהוא שגומר כל הפרשה.1

They pour for him the first cup and here the son asks. If the son lacks intelligence his father teaches him: ‘How different is this night from all other nights? For on all other nights we dip once, on this night twice. On all other nights we eat leavened or unleavened bread, on this night all of it is unleavened. On all other nights we eat meat roasted, stewed or boiled, on this night all of it is roasted. According to the intelligence of the son his father teaches him. He begins with disgrace and ends with praise and they expound ‘my father was a wandering Aramean’ until he completes the whole passage.

Following qiddush and an appetizer course consisting of lettuce and other foods with dips,2 the son asks the father questions. If the son is not developed enough to ask pertinent questions then the father prompts him by pointing out the various ways this meal is different from other evening meals during the year.3 While the general practice at festive meals was to have one course including the dipping of lettuce, on this night there were two.4 On other nights, both leavened and unleavened bread were eaten, but on this night only unleavened. On other nights, meat cooked in a variety of ways would be served, but on this night, it was all roasted.5 The father then teaches ‘according to the intelligence of the son’, beginning with disgrace and ending with praise 6 and expounds the passage beginning with ‘My father was a wandering Aramean’.

The passage in question is the liturgy that owners of land are required by the Torah to say on presenting the first fruits of each year’s crop at the Temple. It is found in Devarim 26:5-8 (I shall hereafter refer to it as parshat habikkurim):

אֲרַמִּי אֹבֵד אָבִי וַיֵּרֶד מִצְרַיְמָה וַיָּגָר שָׁם בִּמְתֵי מְעָט וַיְהִי־שָׁם לְגוֹי גָּדוֹל עָצוּם וָרָב׃ וַיָּרֵעוּ אֹתָנוּ הַמִּצְרִים וַיְעַנּוּנוּ וַיִּתְּנוּ עָלֵינוּ עֲבֹדָה קָשָׁה׃ וַנִּצְעַק אֶל־ד’ אֱלֹקֵי אֲבֹתֵינוּ וַיִּשְׁמַע ד’ אֶת־קֹלֵנוּ וַיַּרְא אֶת־עָנְיֵנוּ וְאֶת־עֲמָלֵנוּ וְאֶת־לַחֲצֵנוּ׃ וַיּוֹצִאֵנוּ ד’ מִמִּצְרַיִם בְּיָד חֲזָקָה וּבִזְרֹעַ נְטוּיָה וּבְמֹרָא גָּדֹל וּבְאֹתוֹת וּבְמֹפְתִים׃ 7

My father was a wandering Aramean, and he went down to Egypt and he dwelt there, few of number, and became there a great nation, mighty and numerous. And the Egyptians did bad to us, and they afflicted us, and they placed upon us hard work. And we cried out to HASHEM the G-d of our fathers, and HASHEM heard our voice, and he saw our affliction and our travail. And HASHEM brought us out of Egypt with a strong hand and an outstretched arm and great terror and signs and wonders.

This passage is a brief synopsis of yetziat mitzrayim, delivered in poetic language and covering all the major points from the entry to Egypt until the final exodus. The job of the father at this stage of the Seder is to expound (doresh) the verses so as to fulfil his obligation to recount the foundational event of the Jewish people.8

It is necessary at this stage to clarify why such a method of expounding the exodus story was chosen. Alternative options would have ranged from simply allowing the father to tell the story in any manner he chose to providing a fixed liturgy containing sections from the Torah and other books of the Tanakh as well as midrashic explanations and embellishments. Part of the answer is that this was Hazal’s default format for liturgy. Many Jews today believe that when saying the Shemone Esrei, for example, they are obligated to use a specific order of words every day, three times a day. However, in reality, Hazal specified only the subject matter of the b’rachot, leaving the precise wording to the choice of each individual or community. The closest we get to a set liturgy is the mandatory inclusion of certain phrases and formulas to be inserted on special occasions. Only short b’rachot were given a fixed text. Variety on a set theme was not an exception for Hazal, it was closer to being a rule.

There is a further reason, however, why this format was so particularly appropriate for the Seder night. The Mishnah states that the father must tell the story ‘according to the intelligence of the son’; it is not enough to tell a story, the story has to be understood, and it has to engage. Given the potential differences in intelligence – from the slow 5-year old to the 12-year old prodigy – among children present at a Seder, let alone the adult participants, even the most perfectly composed text could not fulfil this criterion. A perfectly pitched account of the exodus story for one child would be far too complicated for another and tedious for a third. In order for the ends of the Seder to be achieved, it is necessary that the father be allowed substantial latitude to tell the story in the most appropriate way for his audience.

The question then becomes why any framework was provided at all: why not allow each father complete freedom to tell the story in any way he sees fit? The question might seem odd to the modern Jew who has got used to following a set text even for the most private and personal petitions, but it is worth asking anyway. If Hazal saw fit to specify, up to a point, how the story should be told then there must be a reason. It is not, though, a hard question to answer. The greater the latitude allowed to each father, the greater the chance that, not to put too fine a point on it, he will make a hash of it. The use of a short synopsis of the exodus story places a limit on the discretion of the father, ensuring he covers the main themes of the exodus and gives them their due weight.9

So much, then, for the Seder service as described in the Mishnah. There is nothing in the Gemara that alters this format, however, the Seder service that we use, and that which has been in use for a millennium, looks rather different. The father no longer expounds the verses of parshat habikkurim, instead he reads an exposition that is found in the same form in all of the thousands of different editions of the Haggadah used around the world. This is not to say that the act of darshanut (expounding) is absent, at least in the more learned household, but the object of explanation has shifted from parshat habikkurim itself to the commentary upon it. What apparently has happened is that a standardized way of expounding parshat habikkurim was introduced and accepted, replacing the former latitude to expound the verses with a fixed commentary, known – along with some preliminary material – as the Maggid.10

That is, at least, our guiding assumption, but a little reflection shows it is quite untenable. There is no getting around the conclusion that the introduction of a fixed text – any fixed text – eradicates the possibility of expounding parshat habikkurim according to the intelligence of the son. The standardization of the Shemone Esrei can be said to have the benefits of ensuring that each individual can pray elegantly and in conformity with halachic requirements, even admitting the inevitable cost in terms of kavanah and engagement. The standardization of the Maggid unavoidably undermines the whole enterprise because the goal is communication, not with God, but with another human being.

That would be the case if the Maggid were in every respect perfectly lucid and added up to a riveting account – for those of a given level of intelligence – of the exodus story. The actual text we have in front of us, however, meets neither condition. Look at the following section of the Maggid:

With a strong hand This is the plague, since it says, ‘Behold the hand of HASHEM is on your livestock which are in the field, on the horses, on the donkeys, on the camels, on the cattle and on the flock, a very heavy plague. |

בְּיָד חֲזָקָה זוֹ הַדֶּבֶר, כְּמָה שֶּׁנֶּאֱמַר: הִנֵּה יַד־ה’ הוֹיָה בְּמִקְנְךָ אֲשֶׁר בַּשָּׂדֶה, בַּסּוּסִים, בַּחֲמֹרִים, בַּגְּמַלִים, בַּבָּקָר וּבַצֹּאן, דֶּבֶר כָּבֵד מְאֹד. |

And with an outstretched arm This is the sword, like that which says, ‘And his sword drawn in his hand outstretched over Jerusalem.’ | וּבִזְרֹעַ נְטוּיָה זוֹ הַחֶרֶב, כְּמָה שֶּׁנֶּאֱמַר: וְחַרְבּוֹ שְׁלוּפָה בְּיָדוֹ, נְטוּיָה עַל־יְרוּשָלָיִם. |

And with great terror This is Giluy Shechina, like that which says, ‘Or has God assayed to come to take for Himself a nation from the midst of a nation with trials, with signs, and with wonders, and with war, and with a strong hand, and with an outstretched arm and with great terrors, according to all which HASHEM your God has done for you in Egypt before your eyes.’ | וּבְמוֹרָא גָּדֹל זוֹ גִּלּוּי שְׁכִינָה. כְּמָה שֶּׁנֶּאֱמַר, אוֹ הֲנִסָּה אֱלֹהִים לָבוֹא לָקַחַת לוֹ גּוֹי מִקֶּרֶב גּוֹי בְּמַסֹּת בְּאֹתֹת וּבְמוֹפְתִים וּבְמִלְחָמָה וּבְיָד חֲזָקָה וּבִזְרוֹעַ נְטוּיָה וּבְמוֹרָאִים גְּדוֹלִים כְּכֹל אֲשֶׁר־עָשָׂה לָכֶם ה’ אֱלֹהֵיכֶם בְּמִצְרַיִם לְעֵינֶיךָ. |

And with signs This is the staff, like that which says, ‘And this staff take in your hand, with which you shall do the wonders.’ | וּבְאֹתוֹת זֶה הַמַּטֶּה, כְּמָה שֶּׁנֶּאֱמַר: וְאֶת הַמַּטֶּה הַזֶּה תִּקַּח בְּיָדְךָ, אֲשֶׁר תַּעֲשֶׂה־בּוֹ אֶת הָאֹתוֹת. |

And with wonders This is the blood, like that which says, ‘And I shall place wonders in the heavens and the earth: blood, and fire, and pillars of smoke’. | וּבְמֹפְתִים זֶה הַדָּם, כְּמָה שֶּׁנֶּאֱמַר: וְנָתַתִּי מוֹפְתִים בַּשָּׁמַיִם וּבָאָרֶץ. |

If we leave out the prooftexts and list the ‘explanations’ in order we get the following:

Plague —> Sword —> GiluyShechina —> Staff —> Blood

Who would dare to claim that this, on the face of it, is a reasonable way of telling the exodus story? And yet, this is, quite literally, what the Maggid has to say on the verse beginning ויוצאנו (‘And He brought us out’). Questions abound about what looks disconcertingly like a randomly thrown together list. Why is the fourth plague singled out at the beginning and the first plague mentioned at the end? What is the point of mentioning the staff? What Giluy Shechina (revelation of the divine presence) is being referred to? Most obviously of all, where does ‘the sword’ make any appearance in the story of yetziat mitzrayim.11

In my experience, most observant Jews are vaguely aware of the problem, but will only acknowledge it when pushed and then respond in one of two ways. The first is to claim that the Maggid is an esoteric text full of mysteries. This claim is not falsifiable by any but supernatural means, but one can simply point out that, if it is true, the use of Maggid by ordinary Jews not privy to its secrets should be discontinued post-haste. The second is some variant on the claim that ‘midrash isn’t supposed to make sense’. Without wanting to comment gratuitously on the religious mindset of those who engage in this sort of ‘apologetic’, we can say that even if this were true in general, it cannot be true of the Seder night. The requirement to expound the exodus story using parshat habikkurim as a base and in a way that the child in front of you can understand, is a halachic obligation and that obligation cannot be fulfilled by repeating parrot-like what one acknowledges to be a string of opaque comments arranged higgledy-piggledy.

But if the Maggid as generally viewed appears to be an attempt to do the impossible executed badly, that is not the end of the story. The first chink of light emerges when, it is recognized that while many parts of the Maggid are bafflingly obscure, there are some that are so clear that they practically interpret themselves:

And the Egyptians did bad to us Like that which says, ‘Come let us outsmart him, lest he multiply and when war shall happen he too will be added to our enemies and he will fight against us and go up from the land.’ (Shemot 1:10) | וַיָּרֵעוּ אֹתָנוּ הַמִּצְרִים כְּמָה שֶּׁנֶּאֱמַר: הָבָה נִתְחַכְּמָה לוֹ פֶּן יִרְבֶּה, וְהָיָה כִּי תִקְרֶאנָה מִלְחָמָה וְנוֹסַף גַּם הוּא עַל שֹׂנְאֵינוּ וְנִלְחַם־בָּנוּ, וְעָלָה מִן־הָאָרֶץ. |

And afflicted us Like that which says, ‘And they placed upon it [the people] taskmasters in order to afflict it, and it built storage cities for Pharaoh: Pitom and Rameses’ (Shemot 1:11) | וַיְעַנּוּנוּ. כְּמָה שֶּׁנֶּאֱמַר: וַיָּשִׂימוּ עָלָיו שָׂרֵי מִסִּים לְמַעַן עַנֹּתוֹ בְּסִבְלֹתָם. וַיִּבֶן עָרֵי מִסְכְּנוֹת לְפַרְעֹה. אֶת־פִּתֹם וְאֶת־רַעַמְסֵס. |

And placed upon us hard work Like that which says, ‘And the Egyptians worked the children of Israel with harshness.’ (Shemot 1:13) | וַיִתְּנוּ עָלֵינוּ עֲבֹדָה קָשָׁה. כְּמָה שֶֹׁנֶּאֱמַר: וַיַּעֲבִדוּ מִצְרַיִם אֶת־בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל בְּפָרֶך. |

Unfortunately, by this stage, many Seder participants are so bewildered by the talk of a lady with fully grown breasts rolling around in blood that they have given up trying to understand what is going on. Millions, though, when they reach this section, must have wondered why the entire Maggid couldn’t be so admirably clear. Here, each element of the verse in parshat habikkurim is linked to a verse in the primary account of yetziat mitzrayim in Shemot and they are done so in order. There is no demand here for strained interpretations, everything just makes perfect sense. For one brief part of the exodus story, that of the initial enslavement and oppression of the children of Israel, the tale is told in a way that is easy to understand and communicate. It is not, then, that the author of the Maggid was incapable of expounding the Maggid in a clear and ordered fashion it’s just that, most of the time, he thought it better to strew around random, indecipherable allusions.12

Except, of course, he didn’t. If a text (if anything for that matter) looks mis-executed to this sort of degree, it is worth considering whether you have been looking at it from the wrong angle. In the case of the Maggid, the solution is quite simple: the method of commenting on the verse beginning וירעו by the author of the Maggid is, in essential matters, and despite appearance to the contrary, exactly the same one he uses throughout the work.

What I mean by that is as follows. The purpose of our Maggid is to tell the exodus story in its proper order by linking each successive element in parshat habikkurim to a section of the primary account in Shemot. By turning the verses beginning with ‘A wandering Aramean’ into a map of the Torah’s full account of yetziat mitzrayim, it provides you with a tool for telling the story without missing anything out, but with the flexibility to lengthen or shorten, emphasize or pass over, in accord with the needs of your audience. Once one realizes this, the perplexing list above suddenly becomes entirely clear:

Plague and Sword | Moshe tells Pharaoh that the Hebrews must be allowed to travel into the wilderness lest God ‘strike us with the plague or with the sword.’ Pharaoh responds by intensifying their burden (Shemot 5:3) |

Giluy Shechina | In response to Moshe’s complaint, God tells Moshe that he has not yet been known by ‘my name HASHEM’ and that this name will now be revealed (Shemot 6:2) |

Staff | Aharon throws down his staff at Pharaoh’s court and turns it into a crocodile. (Shemot 7: 10) |

Blood | Moshe and Aharon meet Pharaoh at the river and turn it into blood. (Shemot 7:20) |

To put matters extremely simply, the author divided up parshat habikkurim into 23 parts, divided up the story in Shemot into 23 parts and provided a way of linking the two together, directly where possible, indirectly where necessary.

In the absence of a clear understanding of how the Maggid is supposed to work, readers were forced to make a virtue of necessity and explain the many apparently opaque and confusing features of the text as positive qualities. For example, the Maggid when read off the page famously makes no mention of Moshe whatsoever. This has variously been explained as teaching a theological message about the role of human action in history, as an attempt to prevent the quasi deification of Moshe, or as a way of combatting hypothetical Qaraite services in which Moshe is presumed to have been central. The truth is, however, that there is no good reason when telling the exodus story to omit entirely its most important human character. When we read the Maggid in the correct fashion, however, the problem, like so many others, simply doesn’t arise. The Maggid takes you through the exodus story step by step, dividing up the story into consecutive parts and directing you to relate each part in turn. When using the Maggid to relate the exodus story on Seder night, Moshe is expected to play the exact same role in the story as he does in the Torah itself.

The composition of the Maggid

We are now ready to look in detail at how the Maggid was put together to create a comprehensive map between the synopsis of the exodus contained in parshat habikkurim and the full account contained in the book of Shemot. At this stage, though, it is necessary to sound a sort of warning. The whole purpose of understanding the Maggid correctly is so that it should not be the focus of attention on Seder night. Looking in detail at how the Maggid is put together is useful as a technical exercise and for developing an appreciation of the intellectual powers of its author. Some understanding of how it works is necessary simply to use it properly and to dispel misconceptions about how it is supposed to be used. That done, however, on Pesah, the Maggid should get back behind the scenes, so to speak, and go back to serving its purpose as a tool to help us think and talk about yetziat mitzrayim. If readers of this essay spend their Seder night talking about the Maggid, then it cannot have been said to be a success.

With that said, we can move on with our task. As above, the structure of the Maggid is very simple. It divides up the verses in parshat habbikurim into tiny chunks, then maps them on to a section of the exodus story as told in Shemot. When you put all these chunks in order, you have a complete map of yetziat mitzrayim from beginning to end, that can then be used as a base to expand and contract the story as appropriate on each individual Seder night. The ‘interesting’ part of the Maggid, and that which has generated such a disastrous level of confusion, is the method by which the author linked the tiny chunks of text A to the much larger ones of text B. These links fall into three categories:

(1) Where there exists an obvious thematic and/or linguistic link between the element of parshat habikkurim and the section of Shemot, the Maggid simply links them using the phrase כמה שנאמר, a hard to translate formula found only very rarely in Hazalic literature, amounting to something along the lines of ‘like what as it is said’. 13

(2) Where no such natural link exists, the Maggid will generate one using midrashic exegesis, often cut and pasted from an earlier source. Read on their own, these comments can be quite baffling. Once one realizes that they are not intended to explain or allude to anything, but simply to create a connection to a section of Shemot, then interpretative problems that have survived for a millennium dissolve away.

It should be noted at this point that some of the comments in the Maggid fall somewhere in between the above two camps.

(3) Some of the comments are part of a very basic framework the author of the Maggid inherited from earlier haggadot, taking on a new meaning as part of his system.

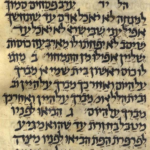

Let’s start by looking at the equivalent section from an earlier Babylonian haggadah:14

The most obvious feature of this Maggid, from our vantage point, is how short it is. The more impatient Seder participant may perhaps find himself pondering whether to use this text as the basis for next year’s service, but this thought would be misplaced for more than just reasons of traditional piety. It is quite inconceivable that this text was ever supposed to be simply read out as it is written.15 Apart from the sparseness of the commentary, the careful reader will have noticed that this Maggid only quotes a little more than half of the words of the parshat habikkurim passage itself!

Instead, it seems obvious that this text was used by those following the original practice of orally expounding parshat habikkurim, the text of which they must have been presumed to know off by heart. The question then becomes why are any comments included at all? The answer, presumably, is that they contain certain themes or claims that the author of the haggadah in question believed were sufficiently important that they should be included at every Seder, regardless of the intelligence of the son or the breadth of knowledge of the father.

A number of these early haggadot have been recovered, in whole or in part, since the discovery of the Cairo Genizah and researchers have been able to group them into identifiable traditions. They all provide the same sparse level of commentary and must all have been used by readers in the same, original, way. There is quite a deal of variety in the midrashic comments included in the different haggadot, but there are three elements that were, as far as we know, universal:

(1) An introductory comment based on ארמי אבד אבי referring to Lavan trying to destroy ‘the whole’.

(2) A comment on ויוציאנו יי ממצרים to the effect that God did not make use of any intermediary during the exodus.

(3) A simple arithmetic explanation of the words ביד חזקה onwards, explaining that they refer to the ten plagues.

While the exact wording differs from one haggadah to another, the basic phraseology is remarkably consistent, indicating a relatively high level of antiquity for these texts. All three elements, along with others that appear in different haggadot, were adopted centuries later by the author of our Maggid and fitted into his system of mapping parshat habikkurim to the account of the exodus in Shemot. When analysing these three comments in particular, it is important to keep two separate questions in mind. The first is what those who originally included these comments in older haggadot had in mind when doing so. The second is what role they play in the Maggid we use. The second question, we will deal with when we look at each individual element of the Maggid in order. The first question, we shall deal with briefly here.

The comment on ויוציאנו is easily explicable in the light of two facts. The first is that during the early Rabbinic period and beforehand there was a widespread belief among parts of the Jewish people in the critical importance of various intermediaries between man and God, and even that some of these intermediaries partook in some way or another of divinity.16 A major focus of the Rabbis during this period was polemicizing against such beliefs.17 The second is that many biblical passages can be read as suggesting that God did make use of intermediaries during the exodus. The most striking among these is the references to המשחית (the destroyer) who was not allowed by God to go into the houses of Jews who had smeared blood on the lintel and doorposts of their house.18 It is for this reason that that the original source for this d’rasha, found in Mechilta D’Rabi Yishmael includes a proof-text derived specifically from the plague of the firstborn. This proof-text is included in some early haggadot and also incorporated by the author of our Maggid.

The d’rasha which uses some simple arithmetic to derive the number 10 from the words beginning from ביד חזקה, is included for an equally obvious though rather different reason. If we imagine a father explaining the verse of parshat habikkurim, we can assume that, whatever his level of knowledge or rhetorical skill, he would have no trouble elucidating the basic meaning of phrases like ‘And he went down to Egypt’, ‘And they placed upon us hard work’, or ‘And HASHEM heard our voice’. However, when he came to the last line he would have had much more difficulty. One can say in general what ‘a strong hand’ or ‘great terror’ means and relate this to the various miraculous acts performed by God prior to the exodus. However, to say anything more specific, to precisely differentiate one from the other, presents a much more difficult proposition. The nature of language such as this is that it evokes more than it can ever be made precisely to say. The purpose of including a simple d’rasha explaining – one might say explaining away – this list of near-synonyms as referring to the ten plagues in their entirety resolves this very practical problem. When the father reaches this point in expounding parshat habikkurim, he knows exactly what he has to talk about, namely the ten plagues.

If the original insertion of these two d’rashot into the haggadah liturgy is reasonably easy to explain, the third one, which forms the first part of the framework built upon by the author of our Maggid, requires greater discussion and represents a suitable jumping off point for looking in detail at each element of the Maggid we use today.

צא ולמד מה בקש לבן הארמי לעשות ליעקב אבינו. שפרעה לא גזר אלא על הזכרים ולבן בקש לעקור את הכל.שנאמר ארמי אבד אבי

There is near-universal agreement among biblical scholars that the correct understanding of this phrase is ‘My father was a wandering Aramean’, though whether it refers to Avraham, Ya’aqov, or to an archetype of the patriarchs in general, is a question regarding which reasonable people will continue to disagree. 19 It is, however, commonly believed that the interpretation ‘according to Hazal’ is ‘An Aramean was trying to destroy my father’, the Haggadah being the proof. Some go so far as to condemn those who side with Ibn Ezra, Rashbam and others as demonstrating impiety. It is easy enough to show that this is not the case. This is the commentary on the verse found in Sifrei: 20

מלמד שלא ירד אבינו יעקב לארם אלא על מנת לאבד ומעלה על לבן הארמי כילו איבדו

This teaches that our father Ya’aqov did not go down to Aram except to wander/perish and it considers Lavan the Aramean as if he destroyed him.

We clearly see here two distinct understandings of the verse. According to the first, the subject of the phrase is Ya’aqov 21 and according to the second it is Lavan. Given the order in which these d’rashot are placed and the use of the phrase ‘it considers’,22 it is reasonable to assume that we are to understand that the first comment follows the basic, literal meaning of the verse23 and that the second is an allusion or hint contained within it. To use an anachronistic classification: the first is p’shat and the second is d’rash. 24

Three questions present themselves. The first is why the d’rasha was made in the first place, the second is why it was included in all early medieval haggadot and the third is what new use, if any, it was put to by the author of our Maggid.

Regarding the first question it is necessary to bear in mind two contexts. One is the tendency among Hazal’s exegetes to depict characters that the Torah portrays as complex and ambiguous as being either wholly good or wholly wicked. Anyone familiar with the commentary of Rashi – whose comments are almost all culled from earlier sources – will be aware of this phenomenon, which can be seen in the treatment of Esau and Bil’am as well as Lavan. The goal seems to have been to draw exemplary moral and immoral archetypes for use in instruction, so Lavan became the archetypal ramai (‘cheat’) used to illustrate a certain form of bad behaviour to generations of Jewish students. The second context is that the term ‘Aramean’ was sometimes used as a casual and broadly derogatory term for non-Jews, similar to the way goy (in essence a neutral description) is used in Yiddish.25 This perhaps reflects tensions with Syrians that would have been become quite acute after the Bar Kokhba revolt, when the land of Israel became a junior part of a large Roman Province with Syria as its political and economic centre. Lavan may have played a similar role to Esau, who was famously used in the midrashic tradition as a target upon which to vent frustrations with the Roman empire and later Christian powers.26

The second question is easy to answer when we look to the passage that is found, with some variation in wording, immediately preceding it in every extant haggadah:

וְהִיא שֶׁעָמְדָה לַאֲבוֹתֵינוּ וְלָנוּ. שֶׁלֹּא אֶחָד בִּלְבָד עָמַד עָלֵינוּ לְכַלּוֹתֵנוּ, אֶלָּא שֶׁבְּכָל דּוֹר וָדוֹר עוֹמְדִים עָלֵינוּ לְכַלוֹתֵנוּ, וְהַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא מַצִּילֵנוּ מִיָּדָם.

And it is that [promise – the covenant between the parts] which has stood for our fathers and for us. For not only one stood up against us to destroy us, but in every generation, they stand against us to destroy us but the Holy One Blessed Be He saves us from their hand.

Kulp (p. 222) characterizes this as teaching that ‘the story of the Exodus is timeless’. Others of a less sympathetic disposition may find here a more than usually reductive rendition of the ‘lachrymose conception of Jewish history’. In any case, the first function of the phrase arami oved avi in the Haggadah is to act as a proof text for this idea: it was not only from Pharaoh that a previous generation was saved, but also from Lavan. The use of the rare phrase צא ולמד (‘go and learn’) as an introduction serves to indicate that the d’rasha about Lavan is a proof for what has come before.27

In this manner, parshat habikkurim is introduced in the Haggadah as a comment, not as a thing commented on. The section beginning צא ולמד therefore serves a dual purpose: it provides support for the theological statement beforehand and introduces the exposition of parshat habikkurim. In other words, it is there to link the preliminary remarks with the central part of the evening. Its function is liturgical, so to speak, ensuring that parshat habikkurim does not enter the evening awkwardly unannounced, but as part of an unfolding order of service.

This is the role that it played in the various different haggadot we have, both from Bavel and the land of Israel. It plays the exact same role in our Maggid. The question is whether it does anything more. As we have said, and as we shall see in unfolding detail, the method of the author of the Maggid was to divide parshat habikkurim and the narrative from Shemot into corresponding sections and link them. Does the comment onארמי אבד אבי fit into this scheme? If it does, then it is instructing the father to pick up the story with Ya’aqov’s return from Aram. This is not in itself far-fetched; if Ya’aqov’s status as an Aramean is taken as a reference to his two-decade stay in Aram, then any kind of explanation of parshat habikkurim would have to mention this, if only briefly.28 There are difficulties, however. In between Ya’aqov’s return and going to Egypt there is lot of narrative material in the Torah that one would have to skip, including his reconciliation with Esau and the unseemly events surrounding Dinah, none of which are relevant to the evening’s theme.

It is important at this stage to bear in mind two things. The first is that, as we saw above, this section is part of a basic framework the author inherited from earlier haggadot. It may be disappointing to find that it fits somewhat awkwardly into his system, but that should not be discounted as a possibility. The second is that this section is fundamentally different from every other part of the Maggid. The format throughout is to quote a fragment from parshat habikkurim then to make some of comment, usually citing a verse and introducing it with כמה שנאמר. This section does the opposite. This may be an indication that what was an introductory passage in earlier haggadot is intended to remain as such in our Maggid, nothing more. More than that we cannot say, except to remark that this section has undoubtedly functioned as a piece of misdirection at the opening of the Maggid, bearing much of the responsibility for sending its readers up interpretative blind alleys.

וירד מצרימה אנוס על פי הדב[ו]ר

The Maggid’s comment, ‘forced, according to the utterance’, is found in all known haggadot from the Land of Israel (though with דיבר or even דבר instead of דבור).29 It was originally inserted into the exposition of parshat habikkurim, presumably, to emphasize that leaving the Land of Israel is not an option a Jew can simply choose to take, but something that may be done only under specified and pressing circumstances. This message, unfortunately, is one that needs to be emphasized in every generation, but was particularly important for the early medieval community in the Land of Israel, struggling for its very existence in the face of Byzantine oppression.

The comment was adopted by the author of our Maggid because it fits in perfectly with his system. Even without citing a verse, it is clear that we are being directed to Ya’aqov’s revelation from God before entering Egypt:

וַיִּסַּע יִשְׂרָאֵל וְכָל־אֲשֶׁר־לוֹ וַיָּבֹא בְּאֵרָה שָּׁבַע וַיִּזְבַּח זְבָחִים לֵאלֹהֵי אָבִיו יִצְחָק׃ וַיֹּאמֶר אֱלֹהִים לְיִשְׂרָאֵל בְּמַרְאֹת הַלַּיְלָה וַיֹּאמֶר יַעֲקֹב יַעֲקֹב וַיֹּאמֶר הִנֵּנִי׃ וַיֹּאמֶר אָנֹכִי הָאֵל אֱלֹהֵי אָבִיךָ אַל־תִּירָא מֵרְדָה מִצְרַיְמָה כִּי־לְגוֹי גָּדוֹל אֲשִׂימְךָ שָׁם׃

And Yisrael journeyed, and all that he had, and he came to Be’er Sheva, and he slaughtered sacrifices to the God of his father Yitzhaq. And God said to Yisrael in visions of the night and He said, ‘Ya’aqov, Ya’aqov,’ and he said, ‘Here I am.’ And he said, ‘I am the God, the God of your father. Do not be afraid to go down to Egypt, for a great nation I shall make of you there.’ (Bereishit 46:1-3).

There are two issues left to resolve. The first is why the author breaks from his normal style and dispenses with the formula of כמה שנאמר followed by a citation. I believe that the answer is that in using his sources and stitching them together in a new way, he adopted the principle of changing the original wording as little as possible and. We will see many further examples of this practice. The second issue is whether it is really plausible to claim that Ya’aqov was forced to go down to Egypt by God’s command, since he was already on the way when he received the revelation. The answer to this, I believe, is that the phrase can be read with an implied comma. Ya’aqov was forced to go down to Egypt by the famine conditions and did so in accordance with direct revelation.

We can also make a brief historical remark at this stage. As mentioned, in its original context in haggadot from the Land of Israel, this comment has an obvious polemic edge. It may, however, have a second one too. In some early haggadot, the comment on ויציאנו יי ממצרים excluding the intervention of any divine or quasi divine entities other than God Himself, has an extra clause לא על ידי דיבר meaning ‘not by means of the logos (‘word’)’. Belief in the logos as an active and separate element within God was a common belief among Hellenized Jews, the most famous of whom was Philo of Alexandria, and eventually became central to Christian theology. I do not believe that the insertion of על פי הדיבר a few lines before לא על ידי דיבר was coincidental.

In logos theology, the ‘word of God’ (or memra in Aramaic) was conceived of as an active and creative force, both separate and yet also part of God, which, while inferior to God Himself, is, from the perspective of human beings, perhaps, ultimately more relevant.30 The opening words of the gospel of John express what was at one stage, unfortunately, a widespread view within the Jewish people before finally being suppressed by the Rabbis of Mishnaic period:

In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was with God in the beginning. Through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made.

The logos was considered to have played an especially important role in the supreme revelation of divine power, the exodus from Egypt, and it is precisely the intervention of any such entity that is denied in the comment לא על ידי דבור. The juxtaposition of the comment stating that Ya’aqov went down to Egypt על פי הדבור seems to me a deliberate attempt to de-personify and demythologize the logos, to turn it back from ‘The Word of God’ into the ‘word of God’. In the exodus story, logos did not do anything (לא על ידי דבור), it did not even say something, it was merely said (על פי הדבור).

ויגר שם