To read this essay as a PDF, click here.

When reading this essay, it is best to have a copy of the Haggadah open in another window.

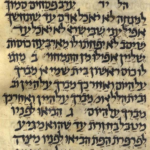

Abstract: The central part of the Maggid in the Haggadah consists of a series of midrashic expositions on parshat habikkurim (Devarim 26:5-9). The purpose of this section is generally understood to be the recitation of the exodus narrative. However, when read as it appears in the Haggadah, this recitation appears to be extremely opaque, open to numerous problems of interpretation, and sometimes inexplicable. This apparent problem can be resolved by revisiting the assumptions one makes before approaching the text. The problems of interpretation are based on assuming that the Maggid’s comments are there to, in some sense, explain Devarim 26:5-9 and that they, when read together, constitute a retelling of the exodus story. In fact, they are nothing more than a way of mapping Devarim 26:5-9 on to the primary account of the exodus story in Shemot and constitute a guide or framework for an oral retelling of the story as recorded there. Once viewed in this way, the Maggid emerges as a sophisticated, yet simple aid to fulfilling the purpose of the Seder and many of the problems that have been raised by commentators can be easily explained.

The final verse expounded in the Maggid is Devarim 26:8.1 Unlike the previous verses, it receives a double exposition. The second links the verse to the ten plagues through some simple arithmetic. The first follows the pattern established in the exposition of previous verses, by taking the individual, and ostensibly tautological, elements in the verse and linking each one to a concept by means of other scriptural texts. The strong hand is linked to plague (דבר); the outstretched arm is linked to the sword (חרב); great terror is linked to the revelation of the divine presence; signs are linked to Moshe’s staff; wonders are linked to blood, presumably that of the first plague.

Looked at from a purely technical or formal perspective, these explanations are, on the whole, readily explicable. The imagery of an extended arm is, on a little reflection, that of one wielding a sword. The particular link between G-d’s hand (albeit without the adjective strong) and plague is established by scripture, perhaps not only in the verse cited.2 The link between the staff and the signs activated by wielding it is equally clear. The connection between wonders and blood is somewhat more tenuous. Based on the verse cited, one could as well claim that wonders refers to fire or smoke.3 Nevertheless, some connection between blood and wonders is established. The least intuitive part is the identification of great terror and the revelation of the divine presence. This is apparently based on a reading of מורא גדול (great terror) as a variant of מראה גדול (a great vision), which is the understanding of Onkelos.4

With the aid of a basic commentary we can, then, appreciate these readings on a technical level. However, when we turn our minds to the purpose of reading the Maggid, things become much less clear. As made plain in the Mishnah (Pesahim 10:4),5 each Jews fulfils his duty to tell the exodus story to his son and others by using parshat habikkurim (the declaration on the first fruits, Devarim 26:5-9), ‘the briefest and yet still comprehensive passage in the Torah which tells the story of the descent into Egypt and the redemption’,6 as a convenient springboard. This retelling of the story must be done ‘according to the understanding of the son’, which might take a few minutes or many hours. The Maggid text as we have it apparently functions as a standardization of this practice, perhaps to help those who cannot confidently expound scripture on their own.

If we take Devarim 26:6 as a paradigm, we can see how the Maggid fulfils its role. Each element in the verse is clearly linked by idea or word to a verse from the opening of Shemot, enabling us to tell the early part of the exodus story concisely and clearly. When we reach the end of the story however, this clarity is replaced by obscurity. Why are two plagues out of the ten, the first and the fourth, picked out for special mention? Why are they in the wrong order? Which revelation of the divine presence is being referred to?7 What is the significance of mentioning the staff? When did the sword, or any sword for that matter, make an appearance during the exodus?

We shall start by attempting to answer the last question, which I believe holds the key to the others and to the proper understanding of the Maggid as a whole.8

Identifying the sword: three approaches

Amongst the Rishonim we find three suggestions explanations of what is meant by the Maggid’s invocation of the sword. Ritva, citing other biblical verses as proof, interprets sword as a metonymical term referring to violence or vengeance in general. Ra’avan suggests that it refers more specifically to the striking of the firstborn, which was, after all, a mass killing. Additionally, the word ‘sword’ is often paired in scripture with the verb ‘to strike’ (להכות), which is also frequently used in relation to the killing of the first born (מכת בכורות). This approach provides an intelligible and plausible reason for the mention of the sword. However, from the perspective of retelling the exodus story it is much less convincing. Why does the Maggid not make things clearer by simply telling us that the outstretched arm refers to vengeance or the tenth plague? It can scarcely be argued that it would be exegetically impossible to create such a connection. If the Maggid is explaining the meaning of the phrase outstretched arm, the introduction of a sword seems like an unnecessary, and therefore confusing, intermediary between text and explanation. Further, such an interpretation of the Haggadah renders its telling of the exodus story even more incoherent, since the tenth macah is made to appear immediately after the fourth (plague) and before the first (blood).

Shibolei haLeqet, Orhot Hayyim and Avudraham9 seek to identify an actual sword involved in the exodus by turning to a midrashic source in Pesiqta d’Rav Kehana which derives an additional element in the exodus story from a hyper-literal reading of the verse in Tehillim למכה מצרים בבכוריהם (read as ‘[praise to] the striker of Egypt by means of their firstborn’).10 According to this midrash, the Egyptian firstborn slew many of their own countrymen in a desperate attempt secure the freedom of the Hebrews and thus avert their own doom. Their sword, or rather swords, therefore played a role in the redemption from Egypt. This explanation faces similarly telling objections to the first. The function of the Maggid is to explain the verses from parshat habikkurim in order to tell the story of the exodus. An oblique reference to an aggadic tale found neither in the Talmud nor Midrash Rabbah would seem an odd way to go about this. At the very least, one would expect a cursory description of the episode.11

The last approach, that of Rashbatz, combines some of the virtues of both these approaches. For the Maggid to be explicable, he requires the sword to reference an actual sword that appears in the exodus story itself. This leaves him with only one option: Shemot 5:3. In this verse, Moshe informs Pharaoh that the people must be allowed to go three days into the wilderness to sacrifice to the G-d of the Hebrews, ‘lest he strike us with the plague or with the sword’. As Rashbatz points out, this has traditionally been understood not as a plea, but as a threat.12 This threat of the sword is what the Maggid intends to draw our attention to.

Though it satisfies the demand for a sword in the exodus story itself, this interpretation seems the least exegetically plausible of all. Why should G-d’s outstretched arm refer to a threat (not even explicitly attributed to G-d) that was never fulfilled? We hardly lack examples of G-d actually executing his power in the narrative. There is, though, an extremely powerful reason to suppose that the Maggid is indeed directing us to Shemot 5:3. As we have already observed, the statement this is the sword is far from the only puzzling thing about this section of the Maggid. Nearly as difficult is its prior identification of the strong hand as the plague. Look again, though, at Shemot 5:3: ‘lest he strike us with the plague or the sword’. The words plague (דבר) and sword (חרב) are placed together frequently only in the books of Ezekiel and Jeremiah, where they always form part of a trio along with famine. Elsewhere, the words are found in the same verse only five times.13 Shemot 5:3 is one of only two occasions (along with Amos 4:10) where plague and sword are directly juxtaposed with plague first and sword second. Since the word sword even by itself appears only twice in the exodus narrative, the allusion on Seder night, for someone well versed in scripture and with his mind on the exodus, is obvious.14

However, we have only succeeded in rendering the exegetical problem more serious. On such an understanding, both the strong hand and the outstretched arm are intended to be a single reference to a mere threat. In order to understand how this can be the case, we need to revise our understanding of how the Maggid operates.

A comment, but not an explanation

As we have already discussed, the purpose of the Maggid is the fulfilment of the obligation to recount the exodus on the night of the 15th of Nissan: והגדת לבנך.15 The Mishnah specifies that this should be done by expounding the declaration said over the first fruits ‘from A wandering Aramean until he finishes the entire section’. This should be done ‘according to the understanding of the son’.18

This is actually a very strange assumption. If the story of the exodus is supposed to be explained ‘according to the understanding of the son’, then specifying the words in which to do this makes no sense. Even the most perfectly lucid explanation could not fulfil this criterion. The elephant in the room, though, is that the Maggid is not lucid at all. It contains numerous opaque references, including apparently borderline-random wordplay, which don’t seem to explain anything. When faced with such ostensible opacity, we should question our primary assumptions.

The exodus is referenced in dozens of places throughout the Tanakh, but the bulk of our information about it is found in Shemot 1:1 – 15:27. The most perfect way to recount the exodus would be to simply read and explain this account, perhaps drawing on outside sources where appropriate. Time constraints obviously make it impossible to follow such a method on Seder night. However, a well-constructed Seder liturgy could try to preserve as many features of this approach as possible. I propose that the purpose of the Maggid’s commentary is not to explain each phrase in parshat habikkurim, but to map them to the primary account in Shemot. This allows each father at the Seder to tell the entire exodus story as it appears in Shemot whilst retaining the flexibility required for the evening. To put it another way, the Maggid is not, as generally assumed, a rendition of the exodus story, but a set of notes indicating how it should be told. We shall see that looking at the Maggid through this prism explains almost every incongruous ‘explanation’ it contains, and answers a number of other questions as well.

We shall start by looking again at the Maggid’s treatment of Devarim 26:6, where the format is almost trivially obvious. We will then demonstrate the power of this approach by applying it to the Maggid’s commentary on 26:8, ostensibly the most obscure part of the Haggadah. Finally, we will look at 26:7 and 26:5. The former fits the theory very well, while necessitating a minor modification. The latter presents some difficulties, though trivial ones compared to the usual way of reading the Maggid.

וירעו אתנו המצרים ויענונו ויתנו עלינו עבודה קשה

The Maggid divides this verse into three sections. The first, And the Egyptians did bad to us, is linked (as usual, by the term שנאמר כמו ‘like that which says’)19 to Shemot 1:10, in which Pharaoh declares to the Egyptians his intention to enslave the children of the Israel. The Maggid is perhaps reading וירעו not as did bad to us, but thought badly of us,20 since Pharaoh cites as his motivation the fear that the Hebrews would side with Egypt’s enemies in future conflicts. We are thus being instructed to recount Pharaoh’s initial plan to enslave the Hebrews after the ascension of a new king to the throne. This is found over three verses: Shemot 8-10.

The Maggid then directs us to the next phase of the story: the actual enslavement. The word they afflicted us is linked to Shemot 1:11, by the presence of the phrase in order to afflict it, from the same root: ע נ ה. Verses 11 and 12 describe how the Egyptians enslaved and afflicted the children of Israel, but found that their new subjects responded by reproducing faster than ever. Finally, the Maggid comments on and they placed upon us hard work by pointing us to Shemot 1:13. In this and the following verse, the Egyptians react by placing even harder work upon the children of Israel. The structure of this section of the Maggid can be represented as follows:

| Phrase in Haggadah | Verses in Torah | Section of story |

| וירעו אתנו המצרים | Shemot 1:8-10 | Pharaoh plans to enslave the children of Israel. |

| ויענונו | 1:11-12 | The children of Israel are enslaved and afflicted. |

| ויתנו עלינו עבודה קשה | 1:13-14 | The Egyptians place hard work on the Hebrews. |

There are three simple principles involved here. First, each phrase is mapped to a section of the exodus story in Shemot. Secondly, the story is told in chronological order. Thirdly, each particle of the verse from parshat habikkurim has to be linked, either semantically or linguistically, to the section of the Shemot story to which is it is mapped. I do not mean to say that the father should simply read all the passages in Shemot being alluded to. Rather, being aware of which section of the story he is being prompted to recount, the father should tell it in his own words, using explanations, commentaries and aggadot, ‘according to the understanding of the son’ (and, of course, his own).

One may ask, at this stage, how different this interpretation of the Maggid is from the traditional understanding, in which the purpose of the cited verses is to explain the elements they are attached to. We shall now apply the same analysis to Devarim 26:8 to see the true power of this method.

ויוצאנו יי ממצרים ביד חזקה ובזרע נטויה ובמרא גדל ובאתות ובמפתים

The Maggid explains the first element of the verse, And HASHEM brought us out of Egypt, with a grandiose declaration that He and not any sub-deity was responsible for the exodus, citing a midrashic explanation of Shemot 12:12.21 Since that verse contains G-d’s declaration that he is about to strike the firstborn, the Maggid, as usually explained, is jumping the gun and directing us to the last plague. However, by following our three interpretative principles, we will see something quite different.

In its comment on the last phrase in the previous verse (Devarim 26:7), the Maggid directed us to Shemot 3:9. In Shemot 3:1-10, G-d reveals himself to Moshe and declares that Moshe shall be His emissary in the liberation of His people. According to our method, if we read on, we should find a passage that is linked to And HASHEM brought us out of Egypt through the Maggid’s emphatic declaration that He alone was responsible. In fact, we find exactly that. Moshe makes the following enquiry of G-d:

…הנה אנכי בא אל בני ישראל ואמרתי להם אל-הי אבותיכם שלחני אליכם ואמרו

לי מה שמו מה אמר אליהם:

… behold, I (will) come to the children of Israel and say the G-d of your fathers sent me to you, and they will say, “What is his name?” What shall I say to them? (Shemot 3:13)

G-d answers the question, apparently, twice. At first, He declares that ‘I will be what I will be’ and instructs Moshe to tell the children of Israel that I will be sent him. However, He immediately follows with a more specific answer:

ויאמר עוד א-להים אל משה כה תאמר אל בני ישראל יי א-להי אבתיכם א-להי אברהם א-להי יצחק וא-להי יעקב שלחני אליכם זה שמי לעלם וזה זכרי לדר דר:

And G-d said further to Moshe, ‘thus shall you say to the children of Israel, “HASHEM the G-d of your fathers, the G-d of Avraham, the G-d of Yitzhak, the G-d of Ya’aqov, sent me to you, this is My name forever, and this is My memorial from generation to generation. (Shemot 3:15)

After extensive discussion, Moshe returns to Egypt. Aharon relays the message, Moshe performs his signs, and the Torah informs us that they were successful:

ויאמן העם וישמעו כי פקד יי את בני ישראל…

And the people believed and they understood that HASHEM had remembered the children of Israel… (Shemot 4:31)

Pharaoh, however, takes a different view:

ויאמר פרעה מי יי אשר אשמע בקלו לשלח את ישראל לא ידעתי את יי …

And Pharaoh said, ‘Who is HASHEM that I should listen to his voice to send away Israel? I don’t know HASHEM …’ (Shemot 5:2)

It is no exaggeration to say that the leitmotif of this part of Shemot is the initial revelation of G-d specifically identified by under his unique name of HASHEM as the sole (or supreme) deity. What appears according to traditional understandings of the Haggadah to be an exclamation of faith awkwardly inserted into the middle of a story, emerges as a prompt to recount an important part of the exodus narrative and discuss arguably its most important theme.

Faced with Pharaoh’s refusal to comply, Moshe and Aharon try a different tack:

ויאמרו א-להי העברים נקרא עלינו נלכה נא דרך שלשת ימים במדבר ונזבחה

ליי א-להינו פן יפגענו בדבר או בחרב:

And they said, ‘The G-d of the Hebrews has happened upon us. Let us go, please, three days travel in the wilderness, and let us slaughter to HASHEM our G-d, lest he strike us with the plague or with the sword. (Shemot 5:3)

As we have seen, the Maggid’s comments on strong hand and outstretched arm are unmistakable references to this verse. The Maggid is, then, directing us to relate the next part of the story in which Moshe and Aharon threaten Pharaoh, after which Pharaoh responds by intensifying the burdens of the children of Israel.

We find further corroboration for this if we look at the source of this section of the Maggid, Sifrei on Bemidbar. The commentaries on strong hand and outstretched arm are both lifted entirely from the same passage in Sifrei, where they appear consecutively. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the Maggid intends the plague and sword to be read as a unit, directing us to a single passage. Modern commentators have puzzled over the fact that the source text, explaining a passage in Ezekiel, is talking about punishments directed not at Egypt, or any other foreign nation, but the Jewish people itself. This is odd if we, as is generally assumed, are supposed to be in the middle of discussing G-d’s vengeance against Egypt.22 However, according to our method of understanding the Maggid, this can be understood without exegetical gymnastics as simply strengthening the allusion to the section of Shemot that the Maggid is directing us to, since it primarily describes Jewish misery.

In its next comment, the Maggid tells us that great terror refers to ‘the revelation of the Shechinah’ (גלוי השכינה). This apparently opaque ‘explanation’ once again becomes clear if we turn to the next part of the story:

וידבר א-להים אל משה ויאמר אליו אני יי: וארא אל אברהם אל יצחק ואל יעקב בא-ל שד-י ושמי יי לא נודעתי להם:

And G-d spoke to Moshe, and He said to him ‘I am HASHEM. And I appeared to Avraham, to Yitzchak, and to Ya’aqov as El Shaddai and (by) My name HASHEM, I was not known to them’. (Shemot 6:2-4)

This is famously one of the hardest passages for traditional p’shat commentary to deal with. After all, as far as we know, G-d was known to all the forefathers as HASHEM. Whatever the correct interpretation of this passage, however, it clearly refers to some revelation of an aspect of G-d by which He had not previously been known or recognized. It is certainly no stretch to refer to this passage as ‘the revelation of the Shechinah’. Once again, the Maggid is directing us to talk about an essential part of the exodus narrative, one that we may justly fear is habitually omitted at the Seder table.

In its fourth comment on the verse, the Maggid tells us that signs refers to Moshe’s staff. If we understand the Maggid as an explanation of parshat habikkurim, this is really quite senseless. The signs, or at any rate some of them, were performed using the staff, but the signs certainly are not the staff itself. However, there is no need to explain away what at first appears to be a simple category error. If we return to Shemot, and read past a genealogical interruption, we find G-d directing Moshe and Aharon to take the staff and turn it into a crocodile23 at Pharaoh’s court, which they promptly do.24 Finally, the Maggid explains that wonders refers to blood. Sure enough, the plague of blood follows immediately after.

After reaching the end of the verse, the Maggid then proceeds to expound it again. According to the traditional way of reading the Maggid, this is odd. No other verse is explained twice. Following our theory, the explanation is quite simple: the Maggid has reached the end of the expounded passage but it has not finished telling the story. It therefore goes back and remaps the verse to the next part of the story, namely the ten plagues.25

We can also understand why in its first rendition of Devarim 26:8, the Maggid refers to verses from outside the primary account of the exodus far more than in its treatment of Devarim 26:5-7. Parshat habikkurim divides the exodus story into four parts: (i) the descent to Egypt, (ii) suffering at the hands of Egyptians, (iii) crying out to G-d and this being accepted and (iv) leaving Egypt by means of signs and wonders. However, in Shemot there is a long narrative in between parts (iii) and (iv) consisting mostly of dialogue between Moshe and the children of Israel, Pharaoh, or G-d (Shemot 3:1 – 6:30). The simple fact that parshat habikkurim completely omits this part of the story necessitates two things. First, the Maggid has to use Devarim 26:8 twice in order to accommodate the extra material. Secondly, since there are no ‘natural’ links between parshat habikkurim and this section of Shemot, the Maggid resorts to roundabout connections, drawing on verses from various parts of the Tanakh. If one reads this section of the Maggid without an awareness of its basic method, many of the ‘d’rashot’ appear, to traditional and academic commentators alike, strange, irrelevant and even incomprehensible.

This new understanding of the Maggid also helps us explain two further puzzling features. First, the Maggid proceeds to inform us that Rabi Yehuda made a mnemonic for the ten plagues. Every commentator struggles with the passage. Rabi Yehuda was one of the greatest of the Tannaim; it does not seem likely that he required a memory-aid to remember basic scriptural information. Leaving that aside, why do we need to be informed of it now, since anyone of a forgetful disposition can presumably just read a few lines up the page? If, however, we understand the Maggid as directing us to tell successive parts of the narrative in Shemot through prompts in parshat habikkurim, the answer becomes simple.

So far, the story has been divided into discrete coherent chunks, clearly identifiable to the reader of Shemot. While it is certainly possible to recount the plagues in pairs or in a simple list of ten, as we have just been directed by the Maggid to do, a fuller explanation requires a different structure. The Torah clearly demarcates the first nine plagues into three sets of three. In each set, the first plague is preceded by Moshe confronting Pharaoh in the morning ‘at the waters’; the second ends with an observation about Pharaoh’s hardened heart and the third is imposed without Pharaoh receiving a prior warning. Each set of three has a theme: the first is the power of G-d to work miracles beyond those of Pharaoh’s necromancers; the second is His placing a distinction between Egypt and Goshen,26 the habitation of the children of Israel; the third is His sending ‘all my plagues … so you may know that there is none like Me in the earth’.27 As some commentators have pointed out, the noteworthy part of Rabi Yehuda’s mnemonic is not the order of the letters, but the way of dividing them up: דצ”ך עד”ש באח”ב rather than, say, דצכ”ע דש”ב אח”ב.28 We can read the Maggid as providing us with two ways of recounting the plagues: either as a list with some basic explanation, or in a more developed way according to the narrative in Shemot, all ‘according to the understanding of the son’.29

Secondly, in the text of Rav Amram Gaon and most subsequent versions of the Maggid, the ten plagues are followed by an odd discussion about the number of plagues at the sea.30 According to our theory, this fills an obvious lacuna in the Maggid up to this point. We have reached the end of the expounded verses, but we have not finished the story. As we have seen, a central feature of the exodus story, both as told in Shemot and understood in the Haggadah, is the revelation and recognition of G-d, identified specifically as HASHEM, as uniquely powerful. The culmination of this thread of the story happens not in Egypt at all, but at the splitting of the sea. Since the Mishnah (Pesahim 10:4) seems to indicate that the Maggid should not stop at Devarim 26:8, but continue until it ‘completes the entire passage’, it would make perfect sense for the Maggid to include a prompt to recount the splitting of the sea. What appears to many to be just the last in a stream of bewildering material, can be understood as an attempt to restore the full exodus story, it having been cut off before the end by the understandable decision not to expound Devarim 26:9 during the years of exile.31

The structure of this section of the Maggid can be expressed as follows:

Phrase in Haggadah | Verses in Torah | Section of story |

ויוצאנו יי ממצרים | Shemot 3:13-5:2 | Moshe learns the name of G-d and reveals it to the children of Israel |

ביד חזקה ובזרע נטויה | 5:3- 6:1 | Pharaoh responds to Moshe’s demands by worsening the burden on the children of Israel. |

ובמרא גדל | 6:2-6:12 | G-d declares that He will hereafter be known as (or by) HASHEM. |

| ובאתות | 7:8-7:13 | Moshe turns his staff into a crocodile at Pharaoh’s court. |

| ובמפתים | 7:14-25 | The plague of blood |

ויוצאנו יי ממצרים ביד חזקה… (2nd time) | 7:14-12:36 | The 10 plagues |

| דצ”ך | 7:14- 8:15 | Plagues of blood, frogs and lice. |

| עד”ש | 8:16-9:13 | Plagues of stinging flies, disease and boils. |

| באח”ב | 9:14-12:36 | Plagues of hail, locusts, darkness and the killing of the firstborn. |

רבי יוסי הגלילי… | 13:1-15:21 | The parting of the Reed Sea. |

Having established this theory as the first coherent way of explaining what is otherwise the most obscure part of the entire Haggadah,32 we shall now discuss the other two verses expounded in the Maggid.

ונצעק אל יי א-להי אבתינו וישמע יי את קלנו וירא את ענינו ואת עמלנו ואת לחצנו:

The Maggid divides the verse into five sections. The first three and the last one fit neatly and readily into our theory. In its first comment, the Maggid refers us to the children of Israel crying out to G-d from the midst of their torments. The next comment directs us to the succeeding verse in which G-d hears their cries and remembers his covenant with the avot. In its third comment, the Maggid then directs us to the Shemot 2:25, the concluding verse of the passage, reading into the phrase and G-d knew (and apparently making use of a pun),33 a knowledge of the most intimate affairs of the children of Israel. The Maggid thus directs us to tell the exodus story in a clear, chronological manner as it appears in the book of Shemot. The Maggid’s final commentary on the verse is a reference to Shemot 3:8, part of the passage in which G-d tells Moshe of his intention to liberate the children of Israel and take them to the land of Canaan.

Before that, though, the Maggid comments on the phrase our toil by directing us all the way back to Pharaoh’s command, at the end of the first chapter of Shemot, to drown all the male Hebrew babies.34 This seems to contradict clearly the claim that the Maggid is taking us through the story in chronological order. However, once again, we simply have to turn to the book of Shemot to see what the Maggid is doing. The Maggid directs us from and He saw our affliction to 2:25 and from our oppression to 3:8. In between these verses we find the story of Moshe finding a burning bush whilst shepherding his flock, and discovering in it an ‘angel of HASHEM’.

A reference to the drowning of the male babies can be read without difficulty as an allusion to Moshe. The structure of the Maggid here, though, is more sophisticated than that. The first three chapters of Shemot actually contain two separate interwoven stories that are drawn together only at the burning bush. The first is the tale of the enslavement of the children of Israel, their crying out to G-d, and G-d’s recognition of their cry. The second is the story of Moshe’s birth and being placed among the reeds, his being raised at Pharaoh’s court, striking an Egyptian officer, and fleeing to Midian. The Torah tells these stories together in very rough chronological concert. However, they can also be related separately, one after the other, and this would be the easier option for oral storytelling. From And the Egyptians did bad to us until and He saw our affliction, the Maggid maps out the first of these stories. It then directs us to tell the story of Moshe from his birth until the burning bush, before moving on with the narrative.35

We may make two observations at this point. The first is that when the Maggid maps parshat habikkurim to the exodus story, there is a great degree of variance in how narrowly it does so. Sometimes, as with ‘And we cried out to HASHEM our G-d’, it points us to very short passages, even a single verse. In other cases, as with ‘our toil’ we are directed to a passage containing dozens of verses. To a certain extent, the author was surely constrained in his freedom of action by the content of the phrases in parshat habikkurim and the narrative in Shemot. However, we notice that examples of the first type almost always refer us to parts of the narrative without which the story cannot be told at all, whereas the second type refer us to parts of the story that are no doubt important, but can be omitted or shortened without sacrificing basic narrative coherence. These sections can be told at greater or lesser length according to taste. Given that every father at a Seder is constrained both by the time available, and the different levels of intelligence, knowledge and interest among his audience, it is natural that the Maggid makes allowance for discretion in how much time to spend on non-essential parts of the story.

Secondly, it has often been observed that the Haggadah ostensibly omits any mention of Moshe, and many have puzzled over why the Maggid instructs us to recount the exodus story without its central character.36 The whole question is premised on the assumption that the text of the Maggid, read on its own or with an explanation, constitutes a rendition of the exodus story. If so Moshe’s role in the story would, indeed, seem to have been deliberately omitted. However, if we understand the Maggid as dividing up the exodus story as it appears in Shemot into discrete chunks and referring us to each in turn, then the question never arises. By following the Maggid’s directions, we include and give appropriate weight to Moshe’s role in our redemption from Egypt.37

The structure of the Maggid in this section is as follows:

| Phrase in Haggadah | Verses in Torah | Section of story |

| ונצעק אל יי א-להי אבתינו | Shemot 2:23 | The children of Israel cry out to G-d after the accession of a new pharaoh. |

| וישמע יי את קלנו | 2:24 | G-d hears the cry of the children of Israel and remembers His covenant. |

| וירא את ענינו | 2:25 | G-d ‘sees’ the suffering of the children of Israel. |

| ואת עמלנו | 1:15-2:22 | Moshe is rescued from the drowning of the males, raised by Pharaoh’s daughter, kills an Egyptian officer, flees to Midian, becomes a shepherd and finds the burning bush. |

| ואת לחצנו | 3:1-12 | G-d tells Moshe that he is to be His emissary in freeing the children of Israel. |

ארמי אבד אבי וירד מצרימה ויגר שם במתי מעט ויהי שם לגוי גדול עצום

ורב:

The Maggid’s treatment of this verse presents the greatest problems for our theory. One reason is perhaps that, unlike the rest of the Maggid, a significant part of it is taken from Sifrei Devarim on the verse itself. What follows is a provisional explanation of the Maggid’s treatment of this verse.38

The Maggid opens by interpreting the first phrase, non-grammatically, to mean ‘an Aramean was destroying my father’, and points us to Lavan pursuing Ya’aqov. It is widely assumed that, in so doing, it is echoing (if not simply quoting) Sifrei. In fact, Sifrei interprets the verse twice: once, in a p’shat manner, as a reference to Ya’aqov, and secondly, aggadically, as a reference to Lavan.39 The Maggid’s decision to cite only the second reading – ostensibly an irrelevant outburst on Seder night – is perhaps an indication of where we should pick up the story: after Ya’aqov’s final exchange with Lavan. If so, we are presumably being directed to recount the Yosef narrative, explaining how the children of Israel came to dwell in Egypt. This is somewhat problematic, though, since in between Lavan’s pursuit of Ya’aqov, and the Yosef story the Torah relates the reconciliation with Esau and the rape of Dinah, neither of which, one would think, have to be included in the Seder night’s story. The explanation for this probably lies in the fact that this statement, or a shorter equivalent formula, is one of the few universal features of earlier skeletal haggadot from both Bavel and the land of Israel. 40 Perhaps the author of the Maggid felt it necessary to include it at the beginning of his version even despite it not being a perfect fit.

The Maggid’s comment on and he went down to Egypt is ‘forced, according to the utterance’.41 This appears to be a reference to Bereshit 46:1-7 in which G-d enjoins Ya’aqov, ‘do not be afraid to go down to Egypt’. In its next comment, the Maggid directs us explicitly to the next chapter when Yosef’s brothers meet Pharaoh and are sent to be shepherds in Goshen. The next comment, on a few people, alludes, albeit indirectly, to Shemot 1-6 in which Ya’aqov’s group is numbered at 70. In its comment on great and mighty, the Maggid directs us to the next verse in which the rapid growth of the children of Israel in their new setting is described.

We have now mapped the entire first chapter of Shemot to parshat habikkurim through the Maggid’s comments. However, there remain two comments which appear to have no place in our system. The first, on and he became there a nation, is indeed problematic. It can be read quite easily as an editorial commentary, but this would be out of keeping with the format of the Maggid as we have described it. We note that this comment is one of only two in the entire Maggid that is taken word for word from Sifrei.42 Perhaps the author of the Maggid thought it an important and authoritative piece of information that must be included in the Seder night’s narrative of the exodus. It is also possible that it is an addition to the Maggid made by a someone working from Sifrei who was not conversant with the method of the original author. Alternatively, the Maggid may be directing us to flesh out one of the sparser parts of the story with some aggadic detail. There may, of course, be some other explanation that I have not thought of.

The Maggid’s other anchorless comment, however, on numerous, is easier to explain. The Maggid here refers us to a verse from an allegorical passage in the book of Ezekiel, linked by the root ר-ב. It is at this point that many Seder participants simply give up on trying to understand what is going on. The sense of confusion is heightened by the fact that modern haggadot quote two verses (16:7 and 16:6) in the wrong order. Millions of Jews have probably wondered why a grown woman with fully formed breasts should be rolling around in blood and imagined the passage to be rather more obscene than it actually is. For those in the know, however, it looks like a reference to a midrash in Mekhilta d’Rabi Yishmael in which the verses are also quoted in this order. According to this midrash, G-d gave the children of Israel two mitzvot involving blood – circumcision and the Pesah sacrifice – in order to provide them with sufficient merit to be redeemed.43 However, even those aware of this midrash might be confused as to why the Maggid should direct us to these events, which occurred much later in the story, at this early stage in the recitation.

In fact, in Geonic and medieval haggadot, verse 6 is absent. It was inserted by a later author, probably Yitzchak Luria, in an act of back formation. Instead, as Kulp argues, the Maggid is alluding to a different part of Mekhilta, which uses the verse to demonstrate the great fecundity of the children of Israel.44 This would appear, however, to be a mere repetition of the Maggid’s previous comment on great, mighty. The Maggid, on such a reading, has run the risk of confusing its audience to no real purpose. Following our theory, we can suggest that there is something more to it than that.

The verse quoted ends with a description of the young lady as ‘naked and bare’.45 In its original context this is probably no more than a description of the adolescent Israel’s vulnerability. However, in the above-mentioned passage in Mekhilta, and subsequently in the midrashic tradition, it is taken as description of the Jewish people’s lowly ethical/spiritual state in Egypt.46 The Maggid refers us to this passage in between directing us to Shemot 1:7, which describes their prodigious growth, and 1:8, in which the Egyptians resolve to enslave them. Perhaps the Maggid is thus telling us to add something to the story, which is not present in the biblical text, but which we have good reason to want to include. It is clear that the enslavement of Avraham’s descendants was foreordained for the purpose of manifesting the greatness of G-d to humanity. However, one can object that the suffering of those generations who were born and died in slavery cannot be justified by such a plan. Our conception of G-d as just can most easily be maintained if those who were enslaved as part of G-d’s plan also deserved it. The Maggid is directing us to explain that, while enjoying remarkable demographic growth, the children of Israel succumbed (as they would do on many subsequent occasions) to the temptations of plenty, and fell into sin.

A provisional account of the structure of this section of the Maggid would look like this:

| Phrase in Haggadah | Verses in Torah | Section of story |

| ארמי אבד אבי | Bereshit 33:1-45:28 | The sale of Yosef through to his invitation to the family to settle with him in Egypt. |

| וירד מצרימה | 46:1-7 | G-d instructs Ya’aqov to descend to Egypt and promises to bring back his descendants. |

| ויגר שם | 46:28-47:12 | Ya’aqov’s family are settled in Goshen. |

| במתי מעט | Shemot 1:1-6 | The counting of Ya’aqov’s clan. |

| ויהי שם לגוי | N/A | ? |

| גדול עצום | 1:8 | The children of Israel rapidly expand. |

| ורב | N/A | The children of Israel prosper and fall into sin prior to be being enslaved. |

Conclusion

The Maggid surely has the highest commentary to content ratio of any text in the Jewish canon, possibly of any text in the world. This is a testament to generations of Jews trying to make sense of what seems to be a uniquely opaque text, read just when clarity is called for. Some Jews make a virtue of being bewildered, others search for esoteric meanings, or attempt to piece together a persuasive account by splicing together multiple different commentaries. Many have abandoned using the Maggid altogether, and many more would doubtless follow if they believed themselves permitted to do so.

I submit that the Maggid can be understood as an innovative tool to retell the exodus story whilst adhering to the halakhic framework specified in the Mishnah, one that is both sophisticated and remarkably simple. The Maggid, of course, incorporates material from diverse sources and eras. However, it does so in a coherent way that is more than the sum of its parts.47 To understand the Maggid in such a way, we need only change the basic assumption we make before reading it. Instead of understanding the Maggid’s comments on the elements of parshat habikkurim as explanations of the verses themselves, we should look at them as a midrashic tools to turn parshat habikkurim into a map for recounting the exodus story as told in Shemot. In short, the Maggid is not a commentary, still less a ‘litany’,48 but a set of lecture prompts.

The best evidence for this theory is, I believe, the structure of Maggid itself, as it has been elucidated above. No other interpretative method can so successfully solve the numerous individual problems of interpretation in the text, or render it as a coherent whole. In the second part of this essay, I will explore other possible lines of evidence in support of this theory, as well as reviewing various objections and making some suggestions about why the author of the Maggid would choose to construct his text in such a way.

Footnotes

- I have used the term ‘the Maggid’ throughout to refer to the section of the Haggadah which deals with Devarim 26:5-8, according to the tradition first recorded by the Babylonian Geonim. This is not perfect, but alternatives (such as ‘Midrash Arami Oved Avi’ or ‘Miqra Bikkurim Midrash’) are clumsier and, in the light of what I will explain, actually misleading.

- See Peirush Qadmon in Haggadah Shel Pesah ‘im Peirushei haRishonim: Torat Hayyim (ed. Ketznelenbogen, Jerusalem, 1998) p. 110.

- The apparent absence of fire or smoke in the exodus story is no objection, as we shall shortly see.

- See Rashbatz, Avudraham, Orhot Hayyim, and the two interpretations attributed to Rashi, in Haggadah Torat Hayyim, pp. 113-4.

- The exact status of this obligation is less clear. The opinion that there is a mitzvah d’oraitah to recount the exodus the night of the fifteenth of Nissan became unanimous from Rambam onwards. However, no such mitzvah is mentioned either by the Behag or Rav Sa’adya Gaon in their lists of the 613 mitzvot, or Ibn Gabirol’s poem. There is also no clear proof of the existence of such a mitzvah in the Torah or Hazalic literature.

- J. Kulp, The Schechter Haggadah: Art, History and Commentary (Jerusalem, 2009), p. 215. See pp. 213-5 for alternative theories. See also D. Silber & R. Furst, Go Forth and Learn (Philadelphia, 2011), pp. 1-15 for a series of homiletical neo-midrashic explanations. Some have questioned why Bemidbar 20:15-16 or Devarim 6:21-24 were not chosen instead. The force of this question is doubtful. One of the passages had to be chosen. In any case, we can simply answer that the first does not provide an opportunity to discuss the plagues, while the second does not provide an opportunity to discuss going down to Egypt.

- Three options are suggested in the classic commentaries, which in itself demonstrates that the reference is unclear, see Haggadah Torat Hayyim, pp. 113-5

- This essay was prompted by an incident on Seder night 5777 where I asked to what the sword referred. The cumulative total of sedarim at which those assembled had been present was well in excess of five hundred. Nevertheless, no-one had the first idea. Moreover, it was clear that no-one had ever thought to ask the question.

- This view is also found in a commentary ascribed to Rashbam. See Haggadah ToratHayyim, pp. 114-115.

- This story also appears in subsequent midrashic sources.

- We shall leave aside the question of whether it would be more appropriate for the Maggid to limit its discussion of the exodus to things that incontrovertibly happened.

- Rashi, drawing on Mekhilta D’Rabi Yishmael, states that Moshe really intended the meaning lest he strike you, but modified his language out of respect for the royal office. Ibn Ezra, followed by Sforno, argues that the simple meaning of us includes both the Egyptians and the Hebrews, and therefore constitutes a threat with no modification of language. Bekhor Shor offers a third interpretation, cited by the Hizkuni and Ralbag, according to which Moshe threatened Pharaoh with the loss of his entire slave population at the hands of G-d unless he allowed them to sacrifice in the wilderness.

- Vayiqra 26:25, Amos 4:10, 1 Chronicles 21:12, 2 Chronicles 20:9 and this verse.

- For the contemporary observant Jew, the words דבר and חרב together are mostly likely to conjure up the fourth blessing on the שמע in th eevening. Such an identification was certainly not universal in earlier times.The siddurim of Ba’al haRoqeah and Rav Amram Gaon include thesewords, those of Rambam and Rav Sa’adya Gaon do not.

- See footnote 7.

- M Pesahim 10:4 16 Explanations of the Haggadah generally assume that the Maggid exists to specify the words in which this exposition should be performed.17Amongst halakhic authorities, this seems to be simply assumed. There is a surprising paucity of discussion on how the mitzvah of והגדת לבנך, as opposed to the trappings that surround it, is supposed to be performed. Typically, the halakhic authority will simply state “וקוראין הגדה” (Sefer Hinuch Parshat Bo 21) or”וקורא כל ההגדה”. (Tur and Shulkhan Arukh 473[:7]). Sefer Mitzvot haGadol (Mitzvot Asei 41), Rif and Rosh only detail beginning with ‘shame’ and ending with ‘praise’ according to both opinions in the Gemara and don’t discuss the Maggid proper. The Behag (who doesn’t include והגדת לבנך in his list of the 613 mitzvot) and Mordechai say nothing at all. Commentators, having nothing to comment on, ignore the issue. Rambam, in his commentary on the Mishnah, states, ‘and the d’rash of that parsha is known and famous’, which is possibly meant to be an explicit confirmation of the assumption that the words of the Maggid constitute the exposition of parshat habikkurim through which we perform the mitzvah. Such an assumption is apparently contradicted by what he writes in the Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Hametz u’Matzah 7:1-2, but then subsequently corroborated in 8:3.

- Later versions replace כמו with כמה.

- Or, literally, ‘rendered us bad (in their imagination)’

- The expansion upon Shemot 12:12 is absent from version of Rav Sa’adya Gaon as well as most earlier haggadot from Bavel and the land of Israel.

- D. Arnow, ‘The Sword Outstretched over Jerusalem: A Puzzling Allusion in the Passover Haggadah’, in CCAR Journal: The Reform Jewish Quarterly (2015), pp. 99-100. Arnow also advances his own interpretation, which is an interesting example of esoteric exegesis in modern academic scholarship.

- ‘Tanin’, often rendered as ‘serpent’.

- Note that, in this specific case, the staff and the signs are actually one and the same.

- This also explains why this ‘d’rasha’ on the verse comes second despite it indisputably being much older.

- Shemot 8:18.

- Shemot 9:15

- The commentary of Ritva includes an extensive discussion, though this is apparently an addition of Rav Haviv Toledano. See also the commentary attributed to Rashbam in Haggadah Torat Hayyim, 102.

- For a fuller discussion of the tripartite structure of the ten plagues and how it relates to the Maggid see N. Fredman ‘The Ten Plagues’, Tradition (20:4, 1982), pp. 332-337

- The Siddur of Rav Sa’adya Gaon includes it as an optional appendix. See Kulp, Schechter Haggadah, p. 234.

- J. Kulp states that there is ‘no evidence’ that Devarim 26:9 was ever included in the Maggid: J. Kulp. Schechter Haggadah, p. 214, f. 83. The obvious piece of evidence is what the Mishnah says. It is true that 26:9 does not mark a parsha division according to the Masoretic system, nor is it even the conclusion of the declaration over the Bikkurim. However, it is the end of something, namely the narrative part of the declaration. 26:8 is not the end of anything. See M. First, ‘Arami Oved Avi, Uncovering the Interpretation Hidden in the Mishnah’, Hakirah (13, 2012), pp. 138-9.

This question has become mixed up with the issue of the antiquity of the Seder. Older scholarship assumed that a service resembling that described in the Mishnah was performed in Jerusalem while the temple stood, and reasoned that it would have been appropriate to continue to 26:9. More recent scholarship has demonstrated that the Mishnah describes a ceremony that is of post-temple provenance. However, it does not follow that it would necessarily have been inappropriate to include 26:9. Whilst in its original context “אל המקם הזה” may refer specifically to the temple, it can be just as easily read as referring to the whole land of Israel.

There is, though, some positive evidence against the assumption that the Mishnah intends us to include 26:9, namely the fact that it is absent from all extant copies of haggadot from the land of Israel. We may question whether the documentary record is complete enough to make firm conclusions. The earliest haggadah we have is from the 8th century, by which time the role and status of the Israeli community in world Jewry was entirely transformed. Saying ‘and he brought us to this place’ did not mean the same thing as in previous centuries. More generally, one cannot assume that later Israeli practice accurately reflects Mishnaic era prescriptions on liturgy, since, most obviously with regard to piyyutim, the opposite often appears to be the case. What we can say, however, with reasonable certainty is that the Maggid we use never included the Devarim 26:9. - In his essay ‘”Davar Acher”: On Dual Narrative in the Haggadah’, Rabbi Shmuel Hain asks the same questions I do about this passage and arrives at similar answers to particular questions. His alternative explanation of the passage as a whole, however, is open to the same objection as all other analogous efforts. He believes the Haggadah is trying to communicate a message and that this message was quickly lost and remained that way for nearly a millennium (at least), despite the fact that generations of Jews were reading the Haggadah in fundamentally the right way. The only conclusion we can draw is that the Haggadah is exceptionally unclear. In Hain’s words, ‘the prooftext misdirects the reader’ and ‘the explication of the midrash is further obscured by the midrashic material preceding it’. According to Hain, the Maggid is ‘the finest rabbinic example of an orchestrated, oscillating narrative’, but it was, on his own telling, written in a way that not one in a million Jews appreciated it. I believe the Haggadah is not trying to communicate a message at all, that it is perfectly clear, and that it has simply been read in the wrong way. See pp. 16-18, f. 15, p. 20 and passim.

- The connection to the word our affliction is established by the fact that the root ע-נ-ה, which in the original context of the verse refers to suffering, has a derivative meaning in which in which it refers to sexual congress. In Rabbinic literature, the root is frequently used in this sense and sometimes to mean its opposite: sexual deprivation. See S. Safrai Haggadat Hazal, pp. 137-8.

- It should be pointed out that this comment of the Maggid is an apparent exception to the rule that each element from parshat habikkurim must be connected to the verses it is mapped to linguistically or thematically. Most commentators explain that עמל is connected to children. However, this comment is taken from Sifrei, where it appears without the words, ‘these are the sons’.

- It is arguably more correct to read the account of the drowning of the male babies in Shemot 1:15-22 as part of the story of the children of Israel, not Moshe, but the Maggid does the opposite.

- See D. Henshke, ‘”HASHEM Brought Us Forth From Egypt”: On the Absence of Moses in the Passover Haggadah’, AJS Review (31:1, 2007)

- As Kulp argues, the famous section beginning ‘not by means of an angel…’ should be read as excluding sub- or intermediary deities, not Moshe: Kulp, Schechter Haggadah, pp. 228- 230. This fits in well with our understanding of the comment as referring us to Shemot 3:13-5:2.

Arnow points out that the claim that the Haggadah text completely omits Moshe is something of a myth that derives from an overreading of a statement made by the Gra, which in itself is somewhat hyperbolic and possibly motivated by opposition to Hassidic theologies of the Tzaddik. See D. Arnow, ‘The Passover Haggadah: Moses and the human Role in Redemption, Judaism (55:2006), pp. 5, 16-20. Arnow’s identifications of places where the Haggadah gives a role to human agency are less convincing, but I believe this a result of asking the text to do things it cannot do as result of reading it in the wrong way. - One of the reasons the Maggid has been so chronically misunderstood is that commentators have assumed that all or most of it is taken from Sifrei. Were this to be the case, it would have to be read as a commentary explaining the words in parshat habikkurim. See the sources quoted in Safrai, Haggadat Hazal, p. 66. Modern resources, includingSefaria, perpetuate this mistake (though, since this essay was originally written, they have placed the passage in square parentheses by way of warning).

- Safrai & Safrai argue that Sifrei reads the word arami as referring to place and not a person, so that the verse would read not ‘my father was a wandering Aramean’, but something more like ‘my father was lost in Aram’. See S. Safrai, Haggadat Hazal, p. 131.

- The other two are the famous ‘not by means of…’ comment on ‘And Hashem brought us out from Egypt’ and the derivation of the ten plagues by means of adding up twos.

- This statement is found in earlier haggadot from the land of Israel, as well as the versions of Rav Sa’adya and Rav Amram Gaon. However, it is absent from the haggadah of Rambam and the version attributed to Natronai Gaon, as well as the manuscript from the Schechter collection. If it is, in fact, an intrusion into the Maggid, this would only strengthen my thesis, since it does not follow the formula of the rest of the Maggid. In that case, Ya’aqov’s descent to Egypt would be included when elaborating either the previous or succeeding element of the verse. See Safrai, Haggadat Hazal, p. 271.

- The other being Rabi Yehuda’s mnemonic.

- Mekhilta d’Rabi Yishmael (ed. Berlin, Jerusalem, 1997), p. 15 (Pisha 5).

- In so doing, he was tilting the text towards an interpretation that had already been suggest by others, including Ritva, Avudraham and Orhot Hayyim. See Haggadah Torat Hayyim, pp. 92-3.

- It may be significant that while the Seder of Rav Amram Gaon usually quotes only the first words of a cited verse, here he also quotes the last two. Seder Rav Amram Gaon (ed. Goldschmidt, Jerusalem, 2004), p. 114.

- Note that, according to this reading, the Maggid is drawing on both passages in the Mekhilta, which is in keeping with its author’s evidently formidable grasp of midrashic sources.

- Haggadah scholarship has reluctantly resigned itself to the view that the Maggid is a cut-and-paste job, substantially composed of out of context materials, that doesn’t amount to a great deal. As Kulp puts it, ‘In my opinion it is extraordinarily difficult to speak of the “intention of the Haggadah”. At best, we can speak of the intention of “this specific text” or the intention of the editor who inserted this specific text into the Haggadah’. Kulp, Schechter Haggadah, p. 230 and passim.

- See J. Rovner, ‘Two Early Witnesses to the Formation of the “Miqra Bikkurim Midrash” and Their Implications for the Evolution of the Haggadah Text’, Hebrew Union College Annual (75:2004), pp. 76, 100-101.