Probably the single most characteristically mekori’ist position is that modern tefilin, mezuzot and sifrei Torah are no good, or at the very least extremely inferior, because the klaf they are made from isn’t properly tanned with afaztim (gall nuts), indeed hasn’t been tanned at all. Modern klaf is actually parchment and thus doesn’t meet the gemara’s strict requirements, which are הלכה למשה מסיני.

One reason this position is considered such a no-brainer for the Jewish Originalist is that the classic defense of parchment-klaf was made by Rabbeinu Tam, the archetypal anti-mekori’ist Rishon. His defence is representative of his oeuvre in the priority it gives to accepted practice and creative re-readings of the Talmud Bavli. One might say it is precisely calculated not to convince our kind of Jew. What follows is a two-part defence of normative contemporary practice, arguing that (a) it is certainly preferable to contemporary mekori’ist practice and (b) it is probably preferable absolutely.

Very nice, but it isn’t klaf

Let us start by granting for the time being that the best, or, indeed, only correct way to prepare klaf is by tanning with gall nuts as described in the Talmud Bavli. That isn’t the only requirement for your tefilin to be kosher. Tefilin must be written on klaf, whereas a mezuza should be written on duchsustos, but may also be written on klaf. Everyone agrees that you get klaf and duchsostos by taking the complete skin of the animal and splitting it: one half is klaf and the other is duchsustus. The only problem is: which one? This is a mahloket Rishonim, but the truth is that all the evidence points in one direction, namely that klaf is the thin outer layer peeled away from the rest of the skin (the epidermis or ‘grain’), and duchsustus is what’s left (the dermis and corium). The evidence for this is as follows:

- The term קלף means ‘peel’, which naturally refers to the thin outer layer that is literally peeled off. There is no etymological reason for calling the thick inner layer קלף.

- The term דוכסוסטוס comes from Greek and means either ‘split into two’, ‘difficult to split’ or simply ‘split’. Any of these refer easily to the lower thick layer which can, with some difficulty, be re-split again into thinner layers. Indeed, in contemporary parlance ‘split leather’ is used precisely to refer to what is left when the ‘grain’ (the outer layer) has been peeled off.

- The gemara requires that one writes on klaf on the flesh side and on duchsustus on the hair side. If we understand klaf to be the outer layer, this makes perfect sense, since in both cases you would be writing on the smooth side that was peeled away from the other layer of the skin. If, however, klaf is the inner layer, this would mean writing on the less smooth side of both, for no apparent reason.

- All ancient tefilin that have been discovered are extremely small. It is much more likely that they contained leather made of the the thin outer layer, rather than the thick inner layer.

- The Yerushalmi states that klaf is made בקולף פני העור. This seems clear proof of the etymological argument (1) above 1.

- While the Bavli stipulates that one writes on klaf במקום בשר, the Yerushalmi uses different terminology: במקום נחושתו. This term, which appears to literally mean ‘its copper place’ has two possible explanations. The first is that it means ‘the underside’ (see M Keilim 8:3), the second is it means ‘the smooth side’. In the second case, this must mean that the klaf is the outer layer, since only then can the smooth side and the flesh side be identical. However, even if the first explanation is correct, it is much easier to explain why the term was chosen if klaf is the outer layer, since, in the strict sense, there is no ‘flesh side’ and the term ‘underside’ clearly refers to the opposite side from the hair, which is the top of the skin. Conversely if klaf is the inner layer, the term נחושתו would be unnecesarily ambiguous, since ‘underside’ does not have such an obvious meaning with reference to the under-layer.

It’s possible to raise counter-arguments to any of these points individually, but there really is no evidence from the primary sources pointing in the other direction. So, it would seem that the correct thing to do is to buy tefilin made by taking the epidermis/grain, tan it with gall nuts and then write on it. Problem: you can’t! All properly tanned tefilin ‘klaf’ sold today is made from the inner layer, according to Rambam’s instructions.

There are three reasons for this. The first is that, with very few exceptions, mekori’ists are Rambamists, either explicitly, or implicitly in that they instinctively place the burden of proof on the opinion in any given dispute that disagrees with Rambam. The second is that those who preserved the knowledge of how to tan using afatzim into the modern era were chiefly Teimanim, who followed the Rambam. The third is that Rambam is both the most emphatic and prestigious opponent of using parchment among the Rishonim and so there is a tendency for proponents of klaf meupatz to defer to his judgement on this too.

This is a big problem. Not only are tefilin made from duchsustus pasul, you can’t even use this klaf for mezuza since the text is written on the wrong side! It would seem, then, that the search for authentic tefilin leads us in practice to a dead end, unless you are willing to buy some sheep hides and start experimenting with tanning for yourself. If we stop here, the conclusion is that the dozen or so people who have done that are the only ones on earth who wear kosher tefilin. In the next section, though, I will argue that things aren’t so bad. If you want to wear kosher, nay, mehudar tefilin, you can probably just dig out the normie ones you had before you got radicalised.

A historical detour

At first sight, defending the use of parchment for klaf looks like an uphill climb. The Mishnah makes clear that diftera is invalid for a Megila and this goes a fortiori for סת”ם. Diftera, according to the Bavli, is skin that has been prepared with salt and flour, but not tanned, and parchment hasn’t been tanned. In addition, according to the argument above, parchment isn’t even from the right side of the skin. While Ashkenazi Rishonim held (correctly) that klaf was the outer layer of the skin, this was basically theoretical. The parchment-klaf they actually used is made by taking the whole skin and shaving down both sides. Since the klaf side is very thin, what you are left with is definitely duchsustus, which isn’t even tanned.

However, all is not lost because we have a remarkable source that sheds light on the origin of the practice of using parchment, namely the Iggeret of Pirkoi ben Baboi.

We’ve all met the guy who went to a Yeshiva and ‘learned’ that a kezayit is the size of an egg and then went back to his family seder and told everyone they were doing it wrong by not jamming matzah into their mouth like a mental patient. Well, Pirkoi ben Baboi was the 8th-century equivalent of that. His unusual name has been ascribed to him being originally from Eretz Yisrael or Persia, from which he moved to Bavel where, so impressed with their academies, he became a fanatical exponent of Babylonian supremacy.

His epistle was written to a far-flung Jewish community, probably Kairouan, imploring them to reject the Torah of Eretz Yisrael and instead accept the total authority of the Babylonian Geonate. The easiest way to do this would have been to promote the Talmud Bavli based on its superior comprehensiveness, editing and dialectic to the Talmud Yerushalmi, but this would have created its own problem. Potentially, these communities could have become scholars of the Bavli in their right and established halachic independence, as in due course happened in Spain and Provence. Instead, Ben Baboi chose to argue that תורה שבעל פה resided only in the Yeshivot of Bavel, the true Zion, and to do so he launched a total attack on the community of Eretz Yisrael and their allegedly aberrant practices.

Much of Ben Baboi’s tract is really quite unhinged. He denounces those who deviate from brachot recorded in the Talmud as blasphemers despite unambiguous and copious evidence of variant versions of the brachot within the talmudim. He asserts a categorical prohibition on saying brachot not found in the Talmud, which is pretty bad news for anyone who has said להדליק נר של שבת and ברוך שאמר. He furiously attacks the addition of the verse שמע ישראל to the kedusha oblivious to the reality that the Babylonian ימלוך ה’ is also an addition. He angrily demands the recitation of the kedusha in every repetition of the amidah for no readily apparent reason at all.

On top of this scattergun attack on liturgical customs with as much authentic validity as those of Bavel, Ben Baboi elucidated a strange historical theory. The aberrant customs of Eretz Yisrael had arisen during a time of shmad when Jews were unable to collectively pray according to the correct forms, but for some reason were able to compose and recite elaborate poetical embellishments of amidah. Only in Bavel had there never been persecution (a false premise by the by) and so only there had the correct statutory prayers been preserved. Now that the shmad of Christian rule was over, it was was incumbent on the Jews of Eretz Yisrael to return to their original practices, which they could do by copying what they did in Bavel.

Fortunately, Geonim in the he subsequent centuries did not press the ridiculous claims that Ben Baboi had made in the name of the Geonate. Instead they made sensible criticisms of piyyut that were excessively long, deviated too much from the subject of the bracha into which they were inserted, or dealt with themes inappropriate for public recitation. Certain insertions specifically attacked by Ben Baboi are already included in Amram Gaon’s siddur, and Saadya Gaon was himself a prolific paytan writing beautiful yotzrot for each week of the Babylonian Torah cycle. It was not until centuries later that Ben Baboi’s philistinic liturgical killjoyism made a real impact.

TEY and the parchment question

It wasn’t just the liturgical practices of Eretz Yisrael that Ben Baboi thought fit for libel; he also attacked numerous halachic practices, in some cases engaging in falsification and in others hyperventilating over trivial differences. For our purposes, what is important is a lengthy section he devotes to condemning the Jews of Eretz Yisrael for using parchment to make their Sifrei Torah and tefilin2. Here as elsewhere, Ben Baboi claims that the Jews of Eretz Yisrael lost the correct practice during a time of persecution, and now were sticking to their aberrant מנהג שמד out of obstinate ignorance.

While Baboi’s claim here is not absurd on its face like his theory of the genesis of the Eretz Yisrael liturgy, he is an unreliable witness and there is no reason to take seriously his claim that every Sefer Torah in the land of Israel had to be buried until the Muslim invasion allowed Jews once again to resume their practice. However, we do learn from Ben Baboi something important: the practice of Jews in Eretz Yisrael during the Geonic period was to use parchment, and they maintained this practice despite being aware that others tanned their scrolls with gall nuts and considered parchment improper. In other words, using parchment is Torat Eretz Yisrael.

How can we explain this apparently strange phenomenon? Actually, it’s pretty easy. Because mainstream orthodoxy is so riddled with literal nonsense that actually makes you stupider when you read it it’s quite easy for mekori’ists to get way with propagating claims that have long since been debunked in academic research, as long as they sound scholarly. But it’s not enough to be plausible; you also have to be correct. It took me a few days on Google to solve this particular puzzle, and all I had to do was read some mainstream history on the development of writing technology, which demonstrates that the standard mekori’ist story is false. So, here goes.

A brief history of parchment and scribal leather

Before commencing, it is necessary to dispel a prevalent misconception. The difference between scribal leather (as we shall henceforth call גויל or קלף that is מעופץ) and parchment is absolutely not that the former is preserved by tannins and the latter by lime. The function of lime in the production of parchment is, first, to remove the hair and second to make the skin easier to stretch. While the use of lime allows for the creation of superior parchment and had become common by the Middle Ages, parchment was produced for 1,000 years without lime, and even the high-quality 8th Century Book of Kells was made without it. Conversely, all contemporary makers of scribal leather also use lime to remove the hairs. To make this completely clear: you can make parchment without lime, and you can make scribal leather with lime. Lime is an irrelevant non-issue.

The actual distinction between scribal leather and parchment is follows. Skin is made principally of collagen. This skin is turned into leather by chemical reaction with tannins which combine the collagen strands into longer chains without altering their physical structure. It is turned into parchment by stretching the moistened skin for an extended period so that the collagen all points in the same direction to make a smooth surface for writing. Parchment is not preserved with lime; it is not necessarily preserved with anything: the removal of the oils and traces of flesh from the skin leaves pure collagen, which if kept dry, but not too dry can last indefinitely. Now, onto the history.

The very earliest skins prepared for writing were leather. This is because the mixture in which the skins were soaked at the beginning of their preparation contained lots of tannins and, by the time the hair had been removed, the skin was already tanned. However, with the passage of time, leather-workers realised that by changing the mixture they could produce less tanned skins and that this had a major advantage. These partially tanned skins could be stretched. which, once done, was much better for writing on. Over time, as technology developed, they figured out a way to remove the hair without tanning the skins at all. To simplify matters somewhat, the more you are able to remove fats and flesh residues from the collagen through scraping, the less tannin you need to apply to preserve it (though, to some extent, tannins were simply replaced by rubbing with salt). Similarly, the better you get at preparing a smooth surface, the less you need to make one through tanning.

This discovery changed the nature of writing. Prior to this, papyrus has been in almost every respect a superior writing material to skin. The main advantage of skin was that it was more durable and it was easier for pastoral cultures to produce without having to rely on trade with Egypt. The key development in parchment technology appears to have happened in the early second century BCE in Pergamum, from which the word parchment derives its name.

In Eretz Yisrael, the Dead Sea Scrolls allow us to get a good look at the spread of parchment technology in the late 2nd temple period. The vast majority of scrolls are leather-parchment hybrids, made according to the following method:

The first step was to dehair (or depilate) the unsplit hide, which was typically done by soaking it in water with natural, enzyme-inducing agents that helped to loosen the hair from the skin. Salt, flour, other vegetable-based materials, urine, and dung were commonly used for this purpose, with the lime mixtures so common in later dehairing processes not yet in use for our manuscripts. This process also played a role in cleaning the hide and loosening its fiber structure for easier manipulation. The hair was removed by scraping once it had been soaked and loosened, after which the dehaired skin would be stretched, dried, and worked with a rock or other implements. The final stage of preparation was to dress both sides of the skin superficially (not by soaking or penetration) with a gallic acid tanning solution, which facilitated the permanence of ink when applied, served as a final means of cleaning, and generally made the surface of the skin more attractive and finished-looking. Investigation has shown that, for the Qumran scrolls, a dressing made from gallic vegetable tannins such as the gall apples of acacia trees was the norm.

However, in addition to the leather-parchment hybrid, there were also true parchment scrolls at Qumran, including the fetching ‘Temple Scroll’, which can be instantly distinguished from the others by its more attractive paler colour. Interestingly, this scroll was rubbed with salt that is not local to the Dead Sea indicating that while the community at Ein Feshkha used a more traditional leather-parchment hybrid technology, other groups they were connected to were using the superior modern parchment.

To sum up this section:

- Many hundreds of years before the Mishnah, scribal leather was already a long obsolete technology, replaced by a leather-parchment hybrid.

- This leather-parchment hybrid was replaced across the Mediterranean by true parchment that did not use any tanning agents and this was already in use in Eretz Yisrael in the late 2nd Temple period.

Close your eyes and look again

I am not (shudders) a conservative, but the most important intellectual lesson I ever learned, I heard from Ronald Reagan: “The trouble with our Liberal friends is not that they’re ignorant; it’s just that they know so much that isn’t so”. Nowhere is this lesson more important than in the field of Torah. I would estimate that upwards of 90% of common errors are result of learning things that aren’t true rather than lack of knowledge. Let us now apply this to our topic. Everyone knows that Hazal required use of afatzim to make klaf and gvil, and that therefore at some subsequent point Jews must have stopped using it, whether justified or otherwise. But did they? Let us review the evidence.

- In the Geonic period, the Jews of Eretz Yisrael used exclusively parchment. In addition to the testimony of Ben Baboi and certain references in the Geonim, we have remarkable confirmation of this in the fact that scrolls in the Cairo Genizah from Eretz Yisrael are written on parchment, whereas those from Bavel are on leather.

- The Yerushalmi never once mentions afatzim with respect to the preparation of skins for writing, though it does mention them in the preparation of ink. Neither does Mesechet Sefer Torah or Mesechet Sofrim. Instead, the Yerushalmi simply states הלכה למשה מסיני שיהו כותבין בעורות.

At this point, deeply ingrained habits of Bavlicentrism rear their head and cry out that it’s obvious that Hazal must have have required afatzim. But is it obvious? Is scribal leather superior to parchment? No, obviously it is greatly inferior. It looks worse (when was the last time you brought a book with brown paper?) and it is harder to write on. It is so obviously inferior, in fact, that no-one has used this technology for well over a thousand years except for atavistically minded Jews. Does scribal leather last longer? As long as you don’t dunk your klaf in water for extended periods, not really. Were Hazal unaware of parchment such that it wouldn’t be necessary to mention its unacceptability? No, it had been the premiere writing technology for civilized people in the Mediterranean for hundreds of years before the Mishnah. Indeed, if Hazal had thought for some reason that it was very important to use Iron Age writing technology don’t you think they would have said so? The default assumption once we remove our Rambamism goggles is that Hazal used the best form of skin prepared for writing that they had available. There is no need to posit some event whereby the Jews of Eretz Yisrael chose to switch over to parchment if we don’t first posit based on literally nothing that they fetishized old technology in the first place.

Once we have correctly established our priors, we have a remarkable piece of evidence that settles the matter

רבי פינחס בשם רבי שמעון בן לקיש. התורה שנתן לו הקדוש ברוך הוא למשה נתנה לו אש לבנה חרותה באש שחורה. היא אש מובללת באש חצובה מאש ונתונה באש. הדא הוא דכתיב מימינו אש דת למו

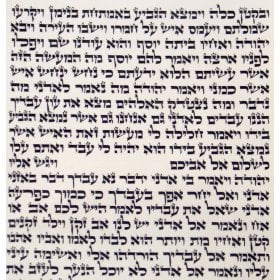

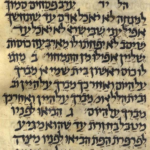

The original Sefer Torah was written with black fire on white fire. Now do you think that when Rabi Shimon ben Lakish came up with this imagery he was looking at something more like this?

Or like this?

Yes, I know, ‘they didn’t see colour in the same way in the ancient world’.3 Let’s save the cope and move on 4.

But what about Bavel?

I have so far argued that the best fit for the evidence we have is that Hazal used parchment gvil and klaf and didn’t see any reason to use afatzim when technological developments meant there was no longer any reason to do so. But what about Bavel? The Bavli does seem to indicate that afatzim are indispensable, and as with Eretz Yisrael, it’s reasonable to assume that the Geonic attitude more or less accurately reflects the position of the Talmudic era. When explaining divergences in Babylonian Jewish practice, there are three general approaches, which aren’t necessarily contradictory:

- Internal-halachic: Perhaps when parchment displaced the use of the earlier leather-parchment hybrid there were Jews who rejected this development for some reason and this position was accepted in Bavel. As a form of reaction to developments in parchment technology, they emphasised that only tanning was important, dispensing with the need for stretching.

- Material culture: Perhaps the new more labour- and water-intensive parchment technology never caught on in Mesopotamia. One important impetus for the rise of parchment in the Mediterranean was a decline in the Papyrus trade from Egypt, but the Marshlands of Iraq are a plentiful local source.5

- Cultural Influence: Zoroastrians or something.

So, it’s a decent question which requires further study, but it need not detain us unduly because we still haven’t got to the big question here.

What is Modern Klaf?

As I have explained, the use of lime to make modern klaf is a non-issue. The absence of afatzim is also a non-issue from a Torat Eretz Yisrael perspective, but there is a still a serious question about the klaf we use today.

Over time, it was discovered that with more prolonged exposure to a tannin-free epilating mixture (whether lime or something else) it was possible to further improve parchment by scraping down both sides to make a very thin collagen sheet which is smooth on both sides. This had major advantages for codexes. In addition, because the epidermis is rich in oils, removing it makes the parchment less susceptible to decay. This medieval parchment is the klaf we use today.

The problem is that, from a halachic perspective this parchment is neither gvil (the whole skin), nor klaf (the epidermis, which is rubbed off early in the process). It is, apparently, duchsustos and though it is certainly super-deluxe AAA duchsustos, you can’t use duchsustos to make tefilin or a Sefer Torah, technically speaking.

And therein lies the rub. As others have pointed out before me, the position of the lenient Rishonim is not that medieval parchment is klaf, it’s that it is as good as klaf. Based on the argument above, this is an eminently reasonable TEY position. Medieval parchment is thin, durable and it has an excellent writing surface, just like klaf, but better. The problems with accepting it have to do with technical issues of canonicity and authority in the absence of a properly functioning halachic system. Personally, I sleep soundly in the knowledge that this debate was hashed out already and the results came in positive. There is, nevertheless, still a reasonable argument for preferring a gvil Sefer Torah, even if it’s brown. There is no argument for splashing out on tefilin to get brown duchsustos over the high-grade stuff.

A cute דבר תורה

Given that the uses of parchment in Eretz Yisrael was a matter of great controversy in the Geonic period, one question that presents itself is why it was omitted from the list of the differences between Eretz Yisrael and Bavel known as ספר חילוקים. The answer to this question may lie in the perspective of the author. Detailed study of different items in his list shows he not only knew Eretz Yisrael practice, but was well versed in its justifications and textual backing. Conversely, he often displays only partial knowledge of Bavli practice and a certain measure of disinterest in working out its rationale. In other words, if Ben Baboi’s nasty, spiteful rant tells us something about the Babylonian attitude to difference, ספר חילוקים tells us not only about differences in practice, but also the Eretz Yisrael perspective on difference in general.

It’s interesting, then, that the liturgical differences between Eretz Yisrael that are the subject of kulturkampf rhetoric in early Geonic texts are absent from ספר חילוקים. Was the author unaware of these differences? It is hard to think so; apparently he just didn’t think they were important. After all, no-one in Eretz Yisrael was saying there was an obligation to spice up the tefilah with poems. Perhaps he just thought that Babylonians weren’t very good at poetry. Similarly, assuming he was aware that Babylonians wrote their סת”ם on leather, perhaps he just thought they weren’t very good at making parchment. Even if he was aware that for some inscrutable reason the Babylonians were insistent on using this old technology, it would be out of place to list such an eccentricity as a difference. After all, there’s no reason to think that in Eretz Yisrael they forbade, or even disapproved of, using afatzim. It’s just … why would you? In one sense, the distinction between Eretz Yisrael and Bavel can be described as the difference between using parchment and scribal leather, but in a more profound sense it is the distinction between thinking that this difference doesn’t matter, and thinking it matters very much.

A lot has been written about what Torat Eretz Yisrael is and isn’t. It’s a bit late to get in the game, but I’ll nevertheless suggest a possible interpretation of במחשכים הושיבני כמתי עולם אמר ר’ ירמיה זה תלמודה של בבל. Here goes: the particular characteristic of the Torah of Darkness is picking fights about things that don’t actually matter at all because you decided that some historically contingent practice represents a dehistoricised eternal Judaism. In other words, it’s going over the top with being a mekori’ist.

Footnotes

- It is true that Ramban makes precisely the opposite inference, but ist is hard to understand his argument.

- Central to his argument is the claim that parchment is considered to be neveilah, which is ridiculous in light of the fact that halacha considers even trampling in skin to be a form of עיבוד.

- Some קלף מעופץ produced today is parchment coloured. This is a combination of it being made using secondary processing of parchment and purified gallnut powder. If prepared in the ‘talmudic’ way, it is always brown.

- There is another interesting piece of evidence. The word גויל in the Mishnah refers to an uncarved stone, so called because the easiest way to move it is to roll it. The use of the term גויל to mean to skins for writing is most easily explained by the fact that, following stretching, parchment has a natural tendency to roll up, and so it most easily stored in rolls. Conversely, scribal leather stays flat.

- This may also explain one of the strangest lines in the Talmud Bavli, in which it edits the Mishnah to remove either מולח or מעבד on the grounds that these are the same melacha. This is very hard to understand until we think in terms of incomprehension caused by differences in preparation of skins for leather. If the Mishnah is listing the tasks necessary to create scribal leather מעבד must refer to tanning, but applying gall nuts and salt are obviously, at least, related at the level of תולדה. However, the Mishnah is not talking about the production of scribal leather, but parchment. Thus מולח is application of salts to remove the hair, מעבד is stretching under tension, and ממחק is scraping of the skin on the frame to remove oils and meat residue, perfectly matching our understanding of the production of parchment in the Mediterranean during this era.

Leave a Reply