Around a year ago, I wrote an article (and a short follow up) arguing that the famous d’rasha of הרגו אין נהרגין, widely believed to be an unimpeachable teaching of Hazal, is, in fact, a דעת יחיד found only in one late, and highly dubious, source recorded in the Talmud Bavli and tacitly ignored by codifiers until the advent of a revolution in the way the Bavli was conceptualized, spearheaded by the scholars of France. I happened upon this analysis while working on one of my unfinished projects, namely an analysis of all the disputes between the Pharisees/Hachamim and Sadducees recorded in the tanaitic corpus and, when I wrote it up into an article and shared it, was under the impression that this was an original discovery of my own, as, indeed, were the generally unsympathetic readers.

It was with a certain pang of disappointment, then, that I found that an article on the subject had already been published in a learned journal all the way back in 2005 by Professor Shamma Friedman. I assumed that he had made the same observations as me, but doubtless with greater attention to detail and I figured that I should probably add a disclaimer that my theory was nothing new.

This turned out, however, to be yet further indication of my inflated sense of self-importance. In fact, I had been pipped to the post not by 15 years, but by something more like 150. My ‘hiddush’ was first proposed by Abraham Geiger and became a commonplace of the ‘rationalist researchers of the 19th and 20th century’, including Hirsch Mendel Pineles, Isaac Hirsch Weiss, Meir Friedman, and Louis Finkelstein, among others. Shamma Friedman, in addition to his other great feats of scholarship, has made something of a sport of overturning the conclusions of earlier scholars, demonstrating through careful analysis that they rest on unsupported assumptions and unsound critical methods, and this is precisely what he has done in this case, providing a robust and thorough defense of the traditional view of Jewry against the dogmas of rationalist Wissenschaft des Judentums. It turns out that, then, that not only was my hiddush old hat, it’s also wrong.

But perhaps not. It is scarcely possible to overstate the respect I have for Shamma Friedman as a scholar. I have personally learned more from him than anyone except mori v’rabi haRav Bar Hayyim, and I recommend his articles as the surest and most efficient way to expand your understanding of תורה שבעל פה. It is my belief, however, that on this issue his analysis is seriously flawed. I will therefore permit myself the liberty of taking up the mantle of the חוקרים ראשונים and attempt to take a swing at the king.

The case for the defence

At the outset, I will list what I take to be the general arguments of Professor Friedman’s article. I strongly urge all readers to study his article in detail before proceeding, in order to confirm that my summing up is accurate and fair (it is also worthwhile to read a subsequent English language article, which contains a shortened version of the same argument in the context of a wider discussion about the distinction between compensation and punitive damages in ancient middle-eastern law and the Torah). By my count, there are four of these arguments:

- The basis for rejecting בריבי’s opinion as authoritative and accurately reflecting earlier practice and legal theory is the view that לא הרגו נהרגין, הרגו אין נהרגין is illogical and contrary to ordinary legal norms. However, this view is based on the anachronistic assumptions of ‘Wissenschaft rationalists’ and, in fact, בריבי’s opinion makes perfect sense in the context of how law operated in the ancient Middle East.

- בריבי’s opinion fits well with the פשוטו של מקרא of the description of עדים זוממים in the Torah.

- בריבי’s opinion fits well with the end result of a process of change in how the mitzvah of עדים זוממים was carried out during the Second Temple period.

- בריבי’s opinion fits well with a close reading of the mishnah upon which it is based.

I will respond to each of these arguments in turn before adding in some further considerations which I believe Professor Friedman has not addressed adequately.

1. The (il)logicality of בריבי’s opinion

One of the great joys of starting a new Shamma Friedman article is knowing that it will demonstrate an astonishing breadth of learning, include painstaking attention to detail, and will be mercifully free of pompous academic claptrap. On the first two scores, his article on עדים זוממים gets the usual full marks, but on the third I have to give it only a B+. Anyone who has hung around in the History department of a university will have heard something like the following kind of claim a few more than umpteen times:

The way we think about logic/law/sex/materials/ gender/religion/cities/countries/numbers/ sexuality/smell/whatever is the product of the Enlightenment/modernity/capitalism/ colonialism/whatever and earlier people conceived of [whatever] in radically different ways that can only be elucidated by me, trained historian.

Sometimes a claim of this sort is really true and justified by evidence, at others it is transparently and completely false. Most of the time, however, it is just kind of overblown. History is a different country, but it’s not inhabited by aliens. Different cultures thought about every conceivable thing in innumerable different ways, but the basic categories of thought are highly consistent, rooted in human biology and unavoidable features of social life. Once we remove certain outliers (like the Amazon tribe that have no concept of numbers), we find a high degree of consistency across civilizations in social and cultural fundamentals, a result of the reality that not all that can be thought of can be made to work. Some cultures have thought it wise and just to punish witches, others have thought it foolish and wrong, but none has ever thought it fit to sentence burglars to eating a slice of chocolate cake.

With that preliminary out of the way, it has to be said that if we take Professor Friedman’s claims on this subject literally, they are demonstrably false. When writing my first article, I was blissfully and shamefully ignorant of the declamations made against בריבי’s opinion by distinguished maskilim. I was very much aware, however, of the long, varied, and famous tradition of apologetic for it within mainstream Rabbinic/orthodox Jewry. The starting assumption of all these explanations is that, on the face of it, לא הרגו נהרגין הרגו אין נהרגין does indeed defy common sense and legal logic. The difference between them and the חוקרים was not whether they thought בריבי’s opinion made sense as a legal ruling, but the respect they had for the Bavli and the degree of willingness they had to employ metaphysical speculation to justify apparently incomprehensible laws. To the names Geiger and Finkelstein we can, then, add Ramban, the Beit Yosef, Bartenura, the Tur, Rav Yaakov Tzvi Mecklenburg, Ran, Malbim, Rabbeinu Behaye, Riva, and Sifthei Hachamim whose basic assumptions about the ‘logic’ of not prosecuting a successful false witness are one and the same. We can say much the same of Rambam who is clearly troubled by the ruling and restricts it, without much in the way of justification in the sugya, to capital cases only and, for good measure, Rashi who felt it necessary to pin the law on an anonymous medieval d’rasha.

It is certainly not true that only a 19th or 20th century rationalist would question the סבירות משפטית of בריבי’s ruling, but, we do not even have to rely on the shared instincts of Rishonim and Aharonim, we need only to look at the ‘בריבי ברייתא’ itself:

תנא בריבי אומר לא הרגו נהרגין הרגו אין נהרגין אמר אביו בני לאו קל וחומר הוא אמר לו לימדתנו רבינו שאין עונשין מן הדין

How much more clear could this be? It does follow logically that, if the false witnesses who almost, but not quite, achieved their goal should be punished according to their intentions, then those that did achieve their goal should receive that same punishment. בריבי’s argument is not that an alternative legal logic applied in Bronze Age societies, but that logic doesn’t apply here at all: אין עונשין מן הדין.

However, while we have sapped Professor Friedman’s argument of much of its rhetorical power, we have perhaps left its fundamental strength unchanged. Nothing of what we have said so far touches on the question of whether the claim of the ‘בריבי ברייתא’ conforms (albeit unbeknownst even to its author) to the realities of legal systems thousands of years before any of the sources we have looked at. It’s time, then, to look at the evidence Professor Friedman presents for how the realities of Bronze Age middle-eastern law can render what for the last 1,000 years has seemed absurd quite reasonable.

Professor Friedman’s argument (presented briefly in the Hebrew language article and at more length in the English one) is based on two clauses of the Ur Nammu code and four from Hammurabi’s. These contains laws that are indeed strikingly similar to the concept of עדים זוממים and his fundamental contention that they provide important contextual information in which to understand the biblical law of punishing false witnesses is entirely plausible. In this specific case, the argument consists of noting that both collections only discuss witnesses who are discovered to be lying during the course of the original trial and are then immediately punished. “There is not a shred of evidence indicating that a trial of the false witness would be opened after the accused was executed.”

It is more than fair to note that, in the hundred or so words quoted by Shamma Friedman from these ancient codes, there is not ‘a shred of evidence’ of very much. It is worth quoting in full the conclusions of other scholars upon which he bases his conclusions:

The last question is whether the false witness was tried at the hearing of the principal case or in a subsequent proceeding. The text says that he has not proved what he said; it does not say merely that his evidence was not believed or accepted by the court. No final answer can be given, since so little is known of Babylonian procedure, but Babylonian justice was certainly not so technical, as that of English law. The plaintiff in a suit might not only lose his action but also be punished for bringing it to the court of trial. It, therefore, seems possible, if not probable, that the court of trial dealt with any question that might arise in the proceedings and itself was competent to try and condemn the witness who has perjured himself.

It scarcely needs to be said that this is not the firmest ground upon which to base far-reaching conclusions. However, it is important at this stage to acknowledge the grain of truth in Professor Friedman’s argument, because once this has been clearly spelled out we can work out exactly where his argument goes wrong.

That grain of truth is as follows: in any conceivable legal system, the vast majority of false witnesses who are discovered will not have been successful in securing the erroneous conviction of an innocent man. This is so, first and foremost, because unless the society is in an advanced state of collapse, most convictions will be correct. On top of that, once the verdict has been rendered, it becomes progressively harder with each passing day to find evidence demonstrating that the original witnesses were lying, and it is reasonable to assume that courts have generally been unwilling to damage their own standing by reopening cases. To put matters in context, the United States has 2.3 million people in prison and 1.3 million lawyers. In 2015, a grand total of 149 convictions were overturned, which was, apparently, a record. In the United Kingdom, four people executed in the years 1950-3 were subsequently pardoned or exonerated. It is very reasonable to assume that in ancient Mesopotamia, where there were no formal appeals courts and no written records of trials, post-trial discoveries of false witnesses were even rarer.

This does not, however, touch on the important point. We can quite readily admit that the majority of cases where עדים זוממים were tried and convicted – in Bronze Age Iraq, in ancient Israel, or anywhere else – fell under the rubric of לא הרגו נהרגין; our question concerns what would happen in the rare (perhaps exceedingly rare) case where a false witness was discovered after his testimony had resulted in the punishment of an innocent man. Let us imagine the following situation. One sunny afternoon in Iraq BCE, 1456, a man is publicly executed after being falsely accused of a heinous crime by a pair of vindictive neighbours and, on their testimony, he is stoned to death in the presence of the town. Present at this execution is the cousin of one of these false witnesses who, wracked with guilt, immediately presents himself before the judges and demonstrates beyond doubt that the witnesses lied and the dead man was innocent. In order for Professor Friedman’s defence of בריבי to work, we must imagine that the judges would tell him and the deceased’s aggrieved family that it was all too late and they would just have to lump it. Not only that, but we must say that in so doing, the judges were not exhibiting their apathy, but faithfully upholding the law of the land. What evidence does Professor Friedman bring for this extraordinary claim? Not a shred.1

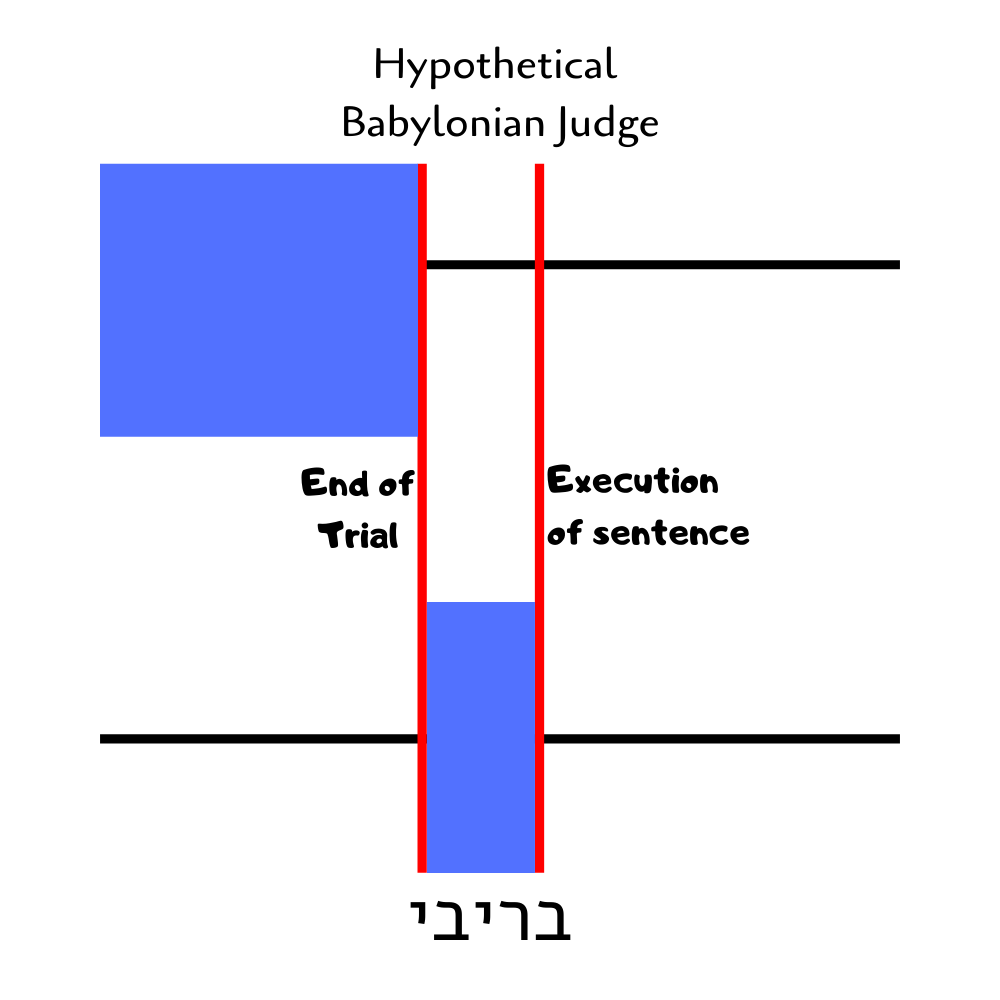

However, let us, for a moment, allow even this leap of faith and accept Professor Friedman’s hypothetical reconstruction of Bronze Age legal categories. If we accept that false witnesses in ancient Mesopotamia could only be punished during the trial itself, how does this vindicate בריבי’s opinion that they could only be tried after the trial had concluded until the actual execution of its verdict? Not only is בריבי’s opinion not the same as the practice of the hypothetical Hammurabic judge, it doesn’t even overlap!

In sum, we can say that contrary to Professor Friedman’s claim we have every reason – 19th century rationalism or no – to look a priori at בריבי’s opinion as being contrary to סבירות משפטית, and no reason to think that it becomes any less so in the light of ancient middle-eastern jurisprudence. I have lingered on this point because, as Professor Friedman himself states, it is really the basis on which the other arguments rest.

2. The Torah’s description of the mitzvah

כִּי־יָקוּם עֵד־חָמָס בְּאִישׁ לַעֲנוֹת בּוֹ סָרָה׃ וְעָמְדוּ שְׁנֵי־הָאֲנָשִׁים אֲשֶׁר־לָהֶם הָרִיב לִפְנֵי יי לִפְנֵי הַכֹּהֲנִים וְהַשֹּׁפְטִים אֲשֶׁר יִהְיוּ בַּיָּמִים הָהֵם׃ וְדָרְשׁוּ הַשֹּׁפְטִים הֵיטֵב וְהִנֵּה עֵד־שֶׁקֶר הָעֵד שֶׁקֶר עָנָה בְאָחִיו׃ וַעֲשִׂיתֶם לוֹ כַּאֲשֶׁר זָמַם לַעֲשׂוֹת לְאָחִיו וּבִעַרְתָּ הָרָע מִקִּרְבֶּךָ׃ הַנִּשְׁאָרִים יִשְׁמְעוּ וְיִרָאוּ וְלֹא־יֹסִפוּ לַעֲשׂוֹת עוֹד כַּדָּבָר הָרָע הַזֶּה בְּקִרְבֶּךָ׃ וְלֹא תָחוֹס עֵינֶךָ נֶפֶשׁ בְּנֶפֶשׁ עַיִן בְּעַיִן שֵׁן בְּשֵׁן יָד בְּיָד רֶגֶל בְּרָגֶל׃

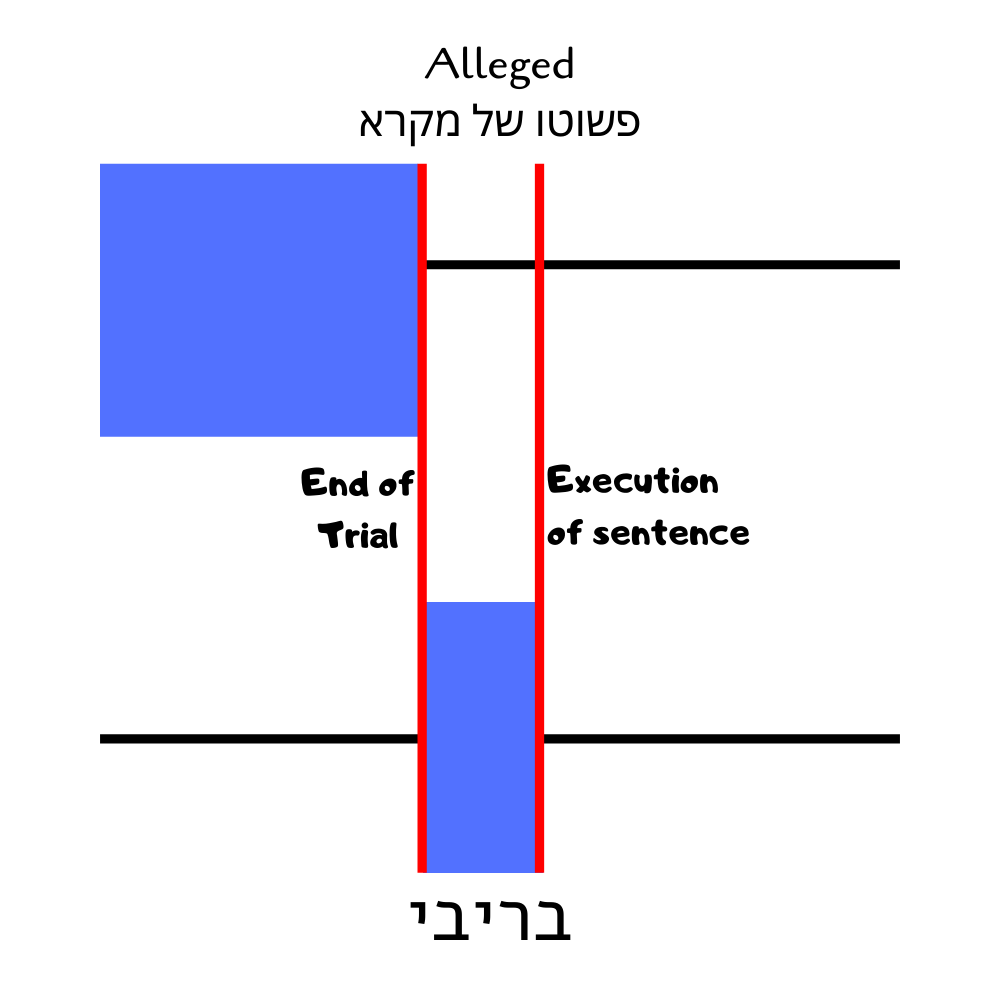

Professor Friedman argues convincingly that the ‘two men’ here are the defendant and the witness who has brought a claim against him. If so, it follows that the Torah is talking about the case when the accusing witness is discovered during the course of the trial, before the object of his false testimony has been convicted of anything. The general language of the passage describes a case of an עד חמס who intended to do harm to his fellow but never succeeded in doing so.

There are some wrinkles here that Professor Friedman himself discusses in detail, but we can overlook them. My answer is the same one I gave to the previous point. It is entirely true that the Torah appears to be talking about a case of a false witness being discovered during the trial who himself is tried and convicted before he was able to inflict harm through his false testimony on another. That is exactly how a false witness would be discovered in the vast majority of cases: דברה תורה בלשון הווה. However, what does this tell us about the rare case when the false witness was discovered only after the end of the trial and the punishment of an innocent man?

Professor Friedman’s answer is essentially the same as בריבי’s: עין עונשין מן הדין. Since the Torah doesn’t tell us what happens in this rare case, we can only assume the false witnesses get off scot free. Is this, however, reasonable? It doesn’t seem reasonable to us, it didn’t seem reasonable to the Rishonim, and it didn’t even seem reasonable to the author of the בריבי ברייתא. We are supposed to believe that some alternative form of logic existed in ancient Israel that would render this explicable, but, even if we could uncover what that was, we wouldn’t be able to understand it. On what basis do we deny logic as we know it?

This is, in fact, a point of fundamental significance. In dozens of cases, the Torah describes laws in the form of a typical or archetypal case. Any school of Judaism that wants to make the Torah into a lived system must deal with the task of applying the Torah’s examples to similar cases in real life. This must always involve deciding what is essential in the Torah’s description of an incident and what is merely incidental. Professor Friedman’s contention, then, properly understood, is that the discovery of the witness during the trial is a fundamental element of the law, without which it cannot operate. But why? The principle of אין עונשין מן הדין was the subject of a dispute even among fourth generation amoraim and, even if we accept it as a given, its ordinary application is very different from how it is allegedly to be used here. My understanding of the passage, and the reasoning it provides for the mitzvah, leads me to believe that the selfsame logic that leads a court to punish a false witness before a conviction, would also move it to punish a false witness after a conviction, when relevant and if possible. In this I have the agreement of – as far as I know – everyone who has ever expressed an opinion on the subject prior to Professor Friedman. His opinion, by contrast, seems to rest on the elision of two distinct concepts: the ordinary operation of the law, and the bounds of the law in extraordinary circumstances.

Finally, we may note that, once again, the interpretation of Devarim 19: 16-21, provided by Professor Friedman, while fitting perfectly with his reconstruction of Bronze Age middle-eastern law, doesn’t actually match בריבי’s opinion.

This brings us, however, to the next stage of the argument.

3. The history of עדים זממים during the Second Temple period

Professor Friedman’s account of the sources that deal with the execution of the law against עדים זוממים during the Second Temple period is masterful, and demonstrates his close attention to, and deep understanding of, linguistic nuance and structural form. This can’t quite obscure the fact that he is working with a single data point, a dispute between Yehuda ben Tabai and Shimon ben Shetah about executing a single עד זומם. However, his account in its broad outlines is almost certainly correct.

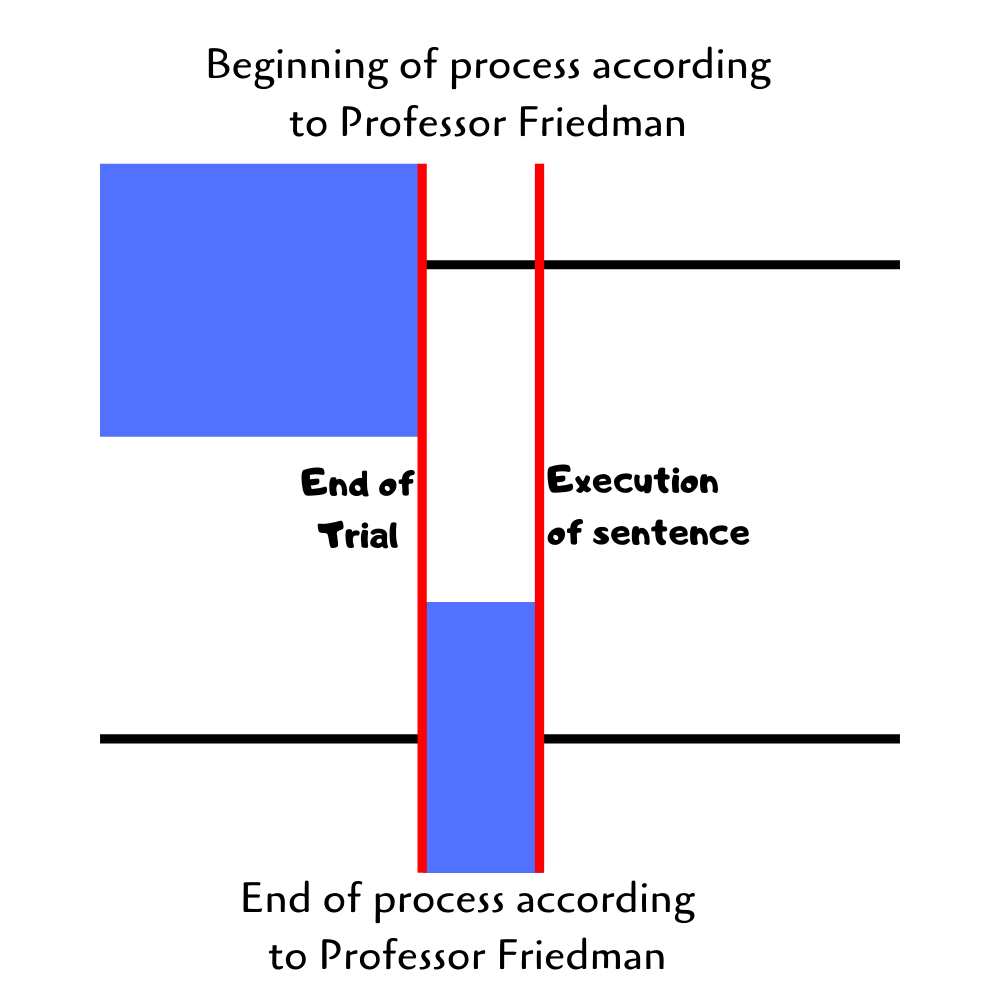

Originally, Professor Friedman argues, a single עד זומם could only be punished if he was discovered at some point during the trial, as a plain reading of the Torah would indicate. However, during the Second Temple period, a process of increasing safeguards was introduced, limiting the application of the law. The end result of this process was that עדים זוממים could only be punished in pairs or more and that they could only be punished after גמר דין, that is to say after their false testimony had resulted in a conviction. His contention is that the seemingly paradoxical position of בריבי is the result of this evolutionary process of the application of the mitzvah. It was always the case that after a punishment of the victim עדים זוממים were exempt, but the earliest point at the which they could be punished was moved forward, leaving only a small window for discovering and prosecuting them in between conviction and the execution of the sentence i.e. what בריבי says.

There is, however, a glaring problem with this argument. The latest point for punishing עדים זוממים at the beginning of the process has become the earliest point for punishing them at the end of it. This means, of necessity, that the latest point must have been pushed back, but Professor Friedman assumes it was only pushed back slightly from גמר דין to the execution of the sentence.

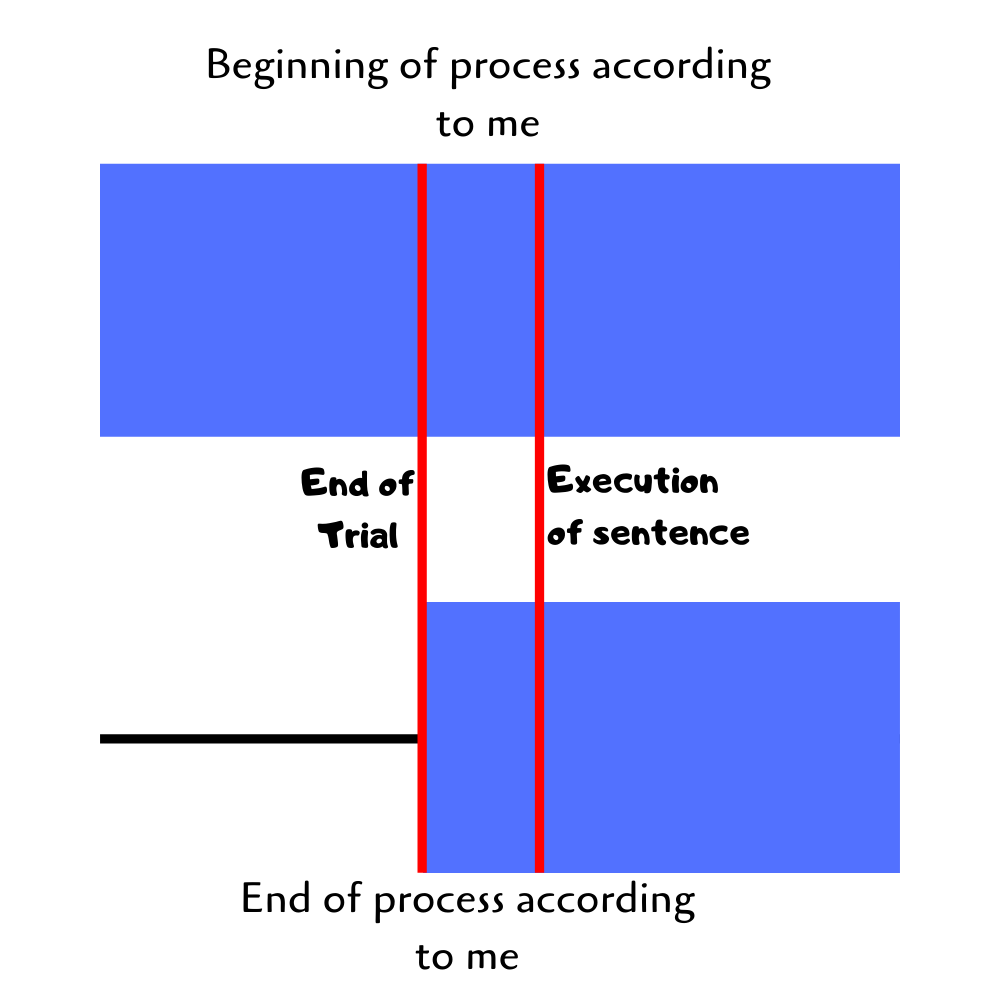

But how plausible is this, really, compared to an alternative in which, originally, there were no time limits – at least in principle – on when an עד זומם could be prosecuted and punished, and in which only the earliest time at which the mitzvah could be applied was changed, which is all that is attested to in the sources?

While the historical data are too scant to demonstrate anything, this version has the significant advantage of requiring fewer ad hoc assumptions to make it work. Ultimately, however, the question of whether בריבי’s opinion is accurate must rest not on guesswork about what happened during the Second Temple period, but on the halacha stated in the Mishnah.

4. The correct interpretation of the mishnah

אֵין הָעֵדִים זוֹמְמִין נֶהֱרָגִין, עַד שֶׁיִּגָּמֵר הַדִּין, שֶׁהֲרֵי הַצְּדוֹקִין אוֹמְרִים, עַד שֶׁיֵּהָרֵג, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר נֶפֶשׁ תַּחַת נָפֶשׁ. אָמְרוּ לָהֶם חֲכָמִים, וַהֲלֹא כְבָר נֶאֱמַר וַעֲשִׂיתֶם לוֹ כַּאֲשֶׁר זָמַם לַעֲשׂוֹת לְאָחִיו, וַהֲרֵי אָחִיו קַיָּם. וְאִם כֵּן לָמָּה נֶאֱמַר נֶפֶשׁ תַּחַת נָפֶשׁ, יָכוֹל מִשָּׁעָה שֶׁקִּבְּלוּ עֵדוּתָן יֵהָרֵגוּ, תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר, נֶפֶשׁ תַּחַת נָפֶשׁ, הָא אֵינָן נֶהֱרָגִין עַד שֶׁיִּגָּמֵר הַדִּין:

Professor Friedman’s interpretation of the mishnah has two components:

- When the hachamim say הרי אחיו קים, this should be taken to mean davka while he is alive and not after he is dead.

- If the hachamim (or the composer of the mishnah putting opinions in their mouth) believed that עדים זוממים could be punished even after their intended victim was executed, they could have interpreted the words נפש תחת נפש in a the same way as the Sadducees. The fact that they resort to a weak d’rasha interpreting these words to refer to גמר דין means that they must have thought that, in fact, once the victim had been executed the window of opportunity was closed.

I must confess that the second of these arguments seems to me wholly unconvincing. The goal of the hachamim in this mishnah is twofold: first to establish that גמר דין is the earliest point for punishing עדים זוממים and, second, to refute the Sadducee opinion that identifies the earliest point as the execution of the sentence. The d’rasha on נפש תחת נפש does both of these jobs in one fell swoop, showing that the Sadducee prooftext is actually a prooftext for the established halacha. Even if we accept Professor Friedman’s characterization of this d’rasha as קלושה at the exegetical level, formally speaking, it is extremely effective. His proposed alternative would significantly weaken the logical position of the hachamim because they would be left without any proof that גמר דין was the earliest point (and surely Professor Friedman agrees that some sort of proof is necessary given his understanding of the פשוטו של מקרא) and a weaker argument versus the Sadducees. The only thing gained would be the removal of any ambiguity about what happened after the defendant was executed, but this assumes – as Professor Friedman has failed to demonstrate – that there is some antecedent reason to believe the witness would be exempt from prosecution.

The first argument, however, does have some force. It is certainly true that the addition of the word אף or אפילו would make the mishnah less ambiguous. Professor Friedman is also clearly correct that a davka reading of the words הרי אחיו קים is the unstated premise of בריבי’s opinion, and the mishnah, at the very least, has not gone out of its way to deny such an interpretation.

This however, brings us to the very crux of the issue. The mishnah clearly tells us what the earliest point for punishing עדים זוממים is. Just as clearly, it does not tell us when the latest point is, or whether, in principle, there is one. Unavoidably, then, our reading of the mishnah must be coloured by our views of what is more reasonable a priori. I have already explained at length why the assumptions brought to the mishnah by גייגר וסייעתו are actually perfectly reasonable. However, even within the internal evidence of the mishnah, I believe there is a clear proof that outweighs the omission of אף before הרי אחיו קים.

The topic of the mishnah, and the only thing it speaks about clearly, is a debate between the sages and the Sadducees about the earliest point at which the עדים זוממים can be punished. The opinion of the Sadducees is that this is the execution of punishment of a maligned defendant. Of course, the Sadducees are wrong, but how can it be taken as a prior assumption of the mishnah, that what to them is the beginning point is actually the endpoint for the mitzvah. Clearly, the Sadducees didn’t believe this themselves! Were it the case, it would mean that the mishnah related only one half of the hachamim-Sadducee debate, while only alluding (at the very most!) to the other half. Surely, the least strained interpretation of the mishnah is that the reason it describes a debate only about the earliest point is because there was no debate about the latest point: both sides agreed that there wasn’t one.2

The authenticity and authority of the בריבי ברייתא

I have argued so far that the rule of לא הרגו נהרגין, הרגו אין נהרגין defies reason not just in the eyes of Wissenschaft des Judentums rationalists, but in those of the medieval Jewish authorities, ordinary common sense and the gemara itself; that it corresponds neither to a plausible reconstruction of Bronze Age middle-eastern jurisprudence, nor to the פשוטו של מקרא of Devarim 19:19, nor to any reconstruction of Second Temple practice, and, finally, that it is based on a tendentious and improbable reading of the Mishnah Maccot 1:6. It is far more likely, as 19th century scholars claimed, that it is a creation of a late stratum of Babylonian rabbinical scholarship which reveled in the paradoxical and sought to wrest an excess of meaning from stray words in earlier rabbinical texts, whose authors intended them to be read with ordinary level-headed judgement. While it is, indeed, true that it would have been extraordinarily rare for any עד זומם to be convicted after his testimony had resulted in the erroneous execution of a defendant, there is absolutely no reason to think that such a possibility was ruled out, in Iraq, in the Torah, in Shimon ben Shetah’s court, in the Mishnah, or anywhere else beyond a 6th century Babylonian’s flight of fancy.

In order to substantiate this argument, it is necessary to return to the בריבי ברייתא itself. Professor Friedman frankly admits that it is of Babylonian origin, but believes it is based upon a ‘deep understanding’ of the mishnah. However, he glides over the very real and obvious problems with the ‘baraita‘. I have already discussed these at length, but to reiterate:

- The baraita is introduced with the formula תנא, but then internally cites another supposed tanaitic source with the formula דתניה. Actually both ‘sources’ must have originated many generations after the tanaitic period.

- The term בריבי means ‘son of Rabi X’, but why would anyone be called that?

- The formula לימדתנו רבינו is used, but makes no sense.

- The argument אין עונשין מן הדין is used as if it is a tanaitic dictum, which it isn’t, and in a context where it isn’t pertinent.

To put matters frankly, this source does not look like it has been carefully composed; either something went wrong during its composition or it was subsequently garbled somewhere in transmission. Bearing this in mind, it is, then, very important to look at the history of its codification as normative halacha. The Rambam included the principle of לא הרגו נהרגין, but sought to neuter it in three ways alien to the בריבי ברייתא: first, by restricting it only to capital cases; secondly, by assigning it the status of מפי הקבלה and, thirdly, by claiming it was based on a reading of the words כאשר זמם לעשות. This clearly demonstrates the problems he had with incorporating this baraita as a legal source. More important for our purposes, though, is what Rif and the Behag did with this source, namely nothing at all. The principle of לא הרגו נהרגין, הרגו אין נהרגין is omitted from both of their digests.

Perhaps, at this stage, Professor Friedman would counter that there was no need for either authority to quote בריבי’s paradox, since it merely recapitulates what the mishnah, which they do quote, has already taught. If so, this certainly will not do. Even those who find Professor Friedman’s exegesis of the mishnah convincing will surely not be so bold as to claim that it is so obvious that any reasonable reader would arrive at it himself without prompting. Certainly, the reading that I have advanced, following 19th and 20th century scholars, is, in the absence of an authoritative statement in the gemara to the contrary, a possible reading. Why do Rif and Behag not, at the very least, avoid room for ambiguity by quoting בריבי?

The simplest explanation is that they do not quote this formula because they did not accept it as binding. This leads us to a discussion of the principles of exclusion and inclusion in the two codes, an unfortunately understudied subject, especially when compared to Mishneh Torah. It is generally known that Rif had the goal of making advanced Torah study more manageable by omitting both aggadic material and שקלא וטריא that is irrelevant to halachic conclusions. However, it is also abundantly clear that he also omitted a significant amount of material that would be defined as halachic in any system of categorization and, if admitted as authoritative, would be of legal significance. Without making too broad a claim, I think it is reasonable to suggest that one of his criteria for omission was material showing signs of late origin and of being, for want of a better word, dodgy. Isn’t it most reasonable to suppose that Rif and Behag viewed this source as an unrepresentative, unreliable and unauthoritative opinion that could be silently passed over in favour of the majority view that there is no arbitrary endpoint for when עדים זוממים are subject to prosecution?

Conclusion

I have attempted here to defend the view of Levi Finkelstein and others regarding the בריבי ברייתא from the revisionist attacks of Professor Shamma Friedman. My arguments can be summed up as follows:

- The paradox stated by בריבי is illogical and contradicts legal norms, not only in the eyes of rationalist scholars, but of a long list of medieval Jewish scholars, who sought to explain away or limit the ruling because of its patent illogicality, and in those of everyone else who has ever read it.

- There is no reason to think that Bronze Age legal codes placed any theoretical limit on the latest time a false witness could be prosecuted, though, as today, their prosecution after the completion of a trial and sentence would have been a rare event.

- While the Torah talks about a false witness being discovered during a trial, there is no reason to think that this is meant to exclude the possibility of one being discovered afterwards and prosecuted.

- According to Professor Friedman’s reconstruction of the historical development of the law of עדים זוממים, the earliest point at which a false witness could be discovered was pushed forward until it eventually arrived at what was originally the latest point at which he could be discovered, which point, therefore, necessarily had to be pushed forward. It is far more reasonable to suppose there never was a latest point.

- Professor Friedman’s interpretation of the mishnah is based on the assumptions that (i) the Sadducee opinion is a fiction of the author, (ii) the author had license to put whatever words he chose into the mouths of the hachamim and (iii) there is antecedent reason to suppose that הרגו אין נהרגין does not operate, and the mere fact that the author did not construct his d’rasha so as to exclude it means that he endorses it. I submit that none of these assumptions is necessarily correct and that it is far more simple to read this mishnah as a dispute about the earliest time a false witness may be discovered, which says nothing about the latest time because neither of the participants thought there was one.

- The fact that the בריבי ברייתא is omitted from the earliest attempts to codify the gemara is most readily explained by the assumption that it was viewed as an unreliable, minority opinion of late origin, contradicting the opinion of earlier sources, and exhibiting strange quirks that indicate either a dubious process of composition or corruption in transmission.

Footnotes

- At this point, we run into the inherent difficulty in the line of argument Professor Friedman is pursuing. His claim is that what appears absurd to us did not appear absurd to them. But if the logic of their position was explicable, it would not appear to us to be absurd.

- Professor Friedman’s argument really hinges on his assumption that the debate is a literary creation originally intended to justify the aberrant decision of Yehudah ben Tabai/Shimon ben Shetah to execute an individual witness. According to him, the composer of the mishnah had complete liberty to reconstruct the debate between the hachamim and the Sadducees in such a way to make his point completely clear. Since he did not write the mishnah in such a way as to completely exclude the opinion of בריבי, he in fact endorses it. Of course, the same goes the other round: since he didn’t write it in such a way to explicitly exclude the interpretation made by Wissenschaft scholars, he in fact endorses that. I do not however, believe we know enough to say how much latitude the author actually had, and to attribute to him what he should have said if he meant this or that. What we can and must do is interpret what he does write as best we can based on assumptions that we can justify.

Dear Gavriel,

Thank you for sending me your incisive article on false witnesses.

Granted that the Mishna is talking about ‘from when’, but once we say והרי אחיו קיים this becomes an absolute determination, whether the Mishna is also addressing this point or not, at least as a source for Bribi. As I wrote in the English article:

The verse “you shall do to him as he schemed to do to his brother/fellow” is interpreted as “his brother/fellow is still alive”. Does this not mean that the author of the Mishnah presents the Pharisees as limiting the punishment of false witnesses to the situation where the accused is still alive, as indeed said in the Babylonian baraita “if they have slain they are not slain”? If so, the baraita should be taken as simply making explicit what the Mishna already says. It was the assumption that the position of the baraita is unique or unreasonable that must have led to explaining the Mishna as meaning ‘even if the accused is alive’, i.e. ‘whether alive or dead’. I propose reexamining the possibility of an absolute determination as the simple meaning of the Mishna, namely it means only when his brother is still alive.

I have elsewhere dealt with the “name” Bribi, in:

מחקרי לשון ומינוח בספרות התלמודית, ירושלים תשע”ד

http://www.kotar.co.il/KotarApp/BrowseBooks.aspx?all

See pp. 355-56 and elsewhere, see index under מכות.

Best wishes,

Shamma Friedman